The advent of any new technology brings with it many inevitable questions, but chief among them all is – what is it like? Human curiosity drives engagement in new experiences. We are now in the age of Virtual Reality (VR) – the very beginning of what could be the next major media format. And the question remains for many – what is it like?

We are now also at the perfect time to understand that experience – biosensor technology has never before been so accessible, and it is perfectly equipped to provide insights into that experience.

Capturing this experience – of an entirely virtual world – is particularly important as it also raises questions about how much our subjective experience can be altered. If we can experience the virtual world the same as we experience the real world, what does this say about the limits of our sensory perception? And what does this mean for the future of VR?

- The Future of VR Testing

- The Science of Fear

- Learning in Virtual Reality

- Training in Virtual Reality

The Future of Virtual Reality Testing

While there has been a great amount of news and discussion surrounding VR, the experimental testing of it, and the answering of these questions, has only just begun.

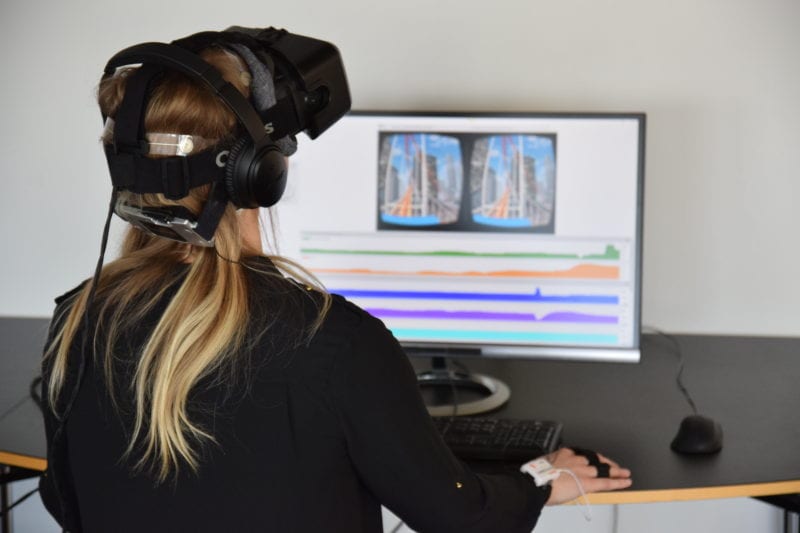

Fortunately, biosensors are up to the challenge. An experience can be difficult (and sometimes impossible) to accurately put into words, whereas biosensors can convert those experiences into data, and tell a more complete story about what’s really going on. These measurements cover a range of bodily signals that convey information about attention, emotion, cognition, and behavior.

Below, we’ve set out three examples of this in action – one study we have completed in-house, and two studies completed by clients (you may also remember our previous case study of feelings of immersion in VR). Each tells us something unique about the experience of VR, helping us come closer to answering the ultimate question – what is it like?

The Science of Fear

The use of VR for horror games offers an entirely new, and terrifying, experience. As the world is entirely immersive and all-encompassing, there is little opportunity to look away or peek through your fingers as you might with a traditional format horror movie (short of taking off the VR headset, of course).

This has been seized upon by VR game developers, hoping to offer an entirely new level of fear to eager players. One of those games in question is The Bellows, available for the HTC vive.

Methodology – VR Research design to test fear

We set out to investigate how EDA (electrodermal activity, otherwise known as GSR) and fEMG could be used to predict the level of fear that the participants were experiencing during the game. The Bellows is well suited to the task, featuring several “jump scare” moments that can be time-locked to biosensor measurements to see what kind of physiological reaction they produce.

EDA was used as a measure of emotional arousal, while fEMG was recorded from the corrugator muscle of the face, and the trapezius muscles at the shoulder / back. The corrugator is activated by furrowing of the brow and can generally be associated with negative valence, while the trapezius has been known to be activated during stress and startle responses.

With the sensors connected, and baseline measurements taken, the participants were strapped in, and set to the task. We looked at the responses to four jump scare moments, which were:

- a loud knock

- a creepy man appearing

- a rat running across the path

- levitating furniture

As they navigated through the task they experienced the four aforementioned jump scare moments, and the activity from each biosensor was recorded.

The Results

The results showed that the corrugator muscle activity (or amount of brow furrow) was largely unaffected by any of the discrete scary moments. The trapezius muscle however was much more indicative of the level of fear, strongly activated when a fearful stimulus was presented.

The trapezius was activated in particular by the loud knock, and the levitating furniture (certainly things to be startled by). It was also found that EDA peaks occurred for all participants when the rat ran across their path, and also with the levitating furniture. It appears that spooky home furnishings are the scariest of all.

Another interesting finding was that relatively decreased trapezius activation was associated with increased gameplay, showing a physiological link between the level of fear (or stress) and exploratory behavior. Those with calm backs appear more ready and willing to explore the world – even if it’s full of levitating chairs and tables.

These metrics can therefore provide information about the level of fear that someone is experiencing, which is not only useful for testing gameplay, but could also potentially be incorporated into the VR experience as feedback to guide the game.

Learning in Virtual Reality

Researchers at Northeastern University (Boston, US) and Niš University (Serbia) investigated the way in which learning and memory can be affected by the environment that the learning takes place in.

They used a laboratory built for such a purpose, equipped with a largely normal learning environment (physical environment; PE), and a Stability and Balance Learning Environment (STABLE) – the latter of which is a virtual environment encompassing several large wraparound screens, with a force plate and motion capture cameras for measuring movement.

Methodology- VR and Learning

The respondents were tasked with shifting their posture in various predefined ways as quickly as possible, in order to successfully complete the trial. The respondents completed several trials, with each one requiring different movements. They also had their EDA measured using a Shimmer sensor, and iMotions to record this while in each environment.

After a period of at least a day, the participants were tested again – either in the same environment as before, or in a different location. The researchers then tested how well retention (how well the memory is kept), and transfer (how well the memory is kept in a new environment).

The Results

The researchers found several particularly interesting results that could impact how we use VR in education. First, the participants who learnt the task in the virtual environment showed a greater memory retention – they were able to remember the posture positions well when tested again. They were also found to be more motivated in the VR condition.

As for memory transfer however, the participants who completed the task first in the normal, real-world environment were more able to remember the posture movements in another environment (in this case in the virtual environment). There was no difference found in the level of engagement between the two groups.

The EDA activity was not significantly different between the two groups, showing that the level of physiological arousal between the two conditions wasn’t different. This goes some way to answering the essential question for this study and VR – what’s it like? Well, it’s just like real life.

What does this mean for VR and education? One way to interpret these results is that to provide transferable knowledge the teaching is best completed in the real-world. It may then be of worth to move this learning experience over to VR, to encourage more motivation and to increase memory retention.

The classrooms of the future might not be entirely virtual, but if research continues to suggest the power of VR in learning, it may well become part of it.

Read more: Getting Started with Virtual Reality in Research

Training in Virtual Reality

Researchers from Aarhus University in Denmark have recently explored the intricacies of motor skill training within VR, through the use of EDA and ECG. The task involved a buzz wire game – in which a metal hoop is held by the participant and is used to trace around a wire – if the hoop makes contact with the wire then a signal will be generated, and the task has to be started again. This can be a delicate task, and is an ideal test of intricate motorics.

The participants were connected to both EDA and ECG devices, and either had to complete this task in the real world, or within VR. While only a pilot study, the preliminary results showed that heart rate decreased throughout the trials, while EDA increased – suggesting that the autonomic nervous system activity generated differing physiological outputs, possibly due to the fast-acting nature of heart rate response, and the slower EDA response.

This proof-of-concept study showed that the methodology was sound and viable – allowing future large-scale research to continue, with further exploration of the nuances of the data. Most importantly, VR was shown to be an accessible medium through which to explore the intricacies of human behavior – even with a task as sensitive as motoric skill training.

Check out: VR: Training and Performance [Part 1]

Conclusion

VR is still an emerging technology and there are many different formats and experiences to explore and test. However, with each new study we can unwrap how virtual experiences differ to our everyday experiences.

While we can’t definitively answer the question of what VR is like from these three study examples, we at least know that biosensors can provide the data to show the way forwards. As iMotions can integrate with any VR headset (even through smartphones), we are able to provide a platform that can help fuel further discoveries.

I hope you’ve found the two studies of VR inspirational for your own research. If you’d like to learn more about how biosensors and iMotions can advance your work with VR, then get in touch!

Download iMotions VR Eye Tracking Brochure

iMotions is the world’s leading biosensor platform.

Learn more about how the VR Eye Tracking Module can help you with your human behavior research