Media consumption is a ubiquitous force in daily life. According to research by Nielsen, the average American spends approximately 11 hours a day consuming different forms of media – around half the day.

It also would of course be of little revelation to state that the media landscape has changed dramatically in the last couple of decades. Whereas viewers would previously watch the TV that was available on the channels that existed (certainly fewer than are available today), media can now be consumed through over-the-top (OTT) services such as Netflix, Hulu, or Youtube TV, for example.

Additionally, media viewers are more likely to engage in dual-screen viewing across TV and mobile phone apps or communications. This creates an increasingly noisy environment in which media creators have to compete in.

These services have also increased the variety of content available to the consumer who is more able and likely to seek out media experiences that fit their specific desires. The increased competition has created an overload of information to the consumer – trying to create a signal that is seen through the noise remains a challenge for those wanting to create great media, or advertise brands in worthwhile and positive ways.

For those looking to improve the experience of a TV program, or improve the success of an ad campaign, there is one aspect essential to success – testing. Testing can give media the cutting edge in this highly competitive environment. Having a better idea of what the audience is after helps set the content on the right track to success.

Traditional media testing research began with interviews and focus groups, and progressed to the inclusion of preference dials (in which viewers indicate their level of enjoyment on a scale in real time).

These methods, while helpful and instrumental in many cases, are also prone to a variety of biases. Viewers are more likely to rate something as positive in the presence of a researcher, or will try and agree with the people they are surrounded by (both of these are forms of social-desirability bias).

While these methods also have their advantages (for example, the best way to check if a viewer remembered a product or a scene is still to ask them), the conscious choice to give an answer ultimately means that the participant is more likely to give inaccurate information (whether they choose to or not).

Clearly the best way forwards, as an advancement from questionnaires and dials, is to test participants in a way that is as objective as possible. Biosensors provide the opportunity to do this, as the signals they create cannot be fabricated, or misled.

Below, we will go through four of the most common methods used in media testing, and discuss the information that they can provide about the success of different types of media.

Eye Tracking

The ability to see what people are looking at is an essential first step in understanding how they experience different forms of media. Eye tracking is an easily implemented technique for recording and measuring visual attention.

As a completely non-invasive method, eye trackers can be placed in front of a screen to see how a participant shifts their attention, all without interfering with their experience. Eye tracking glasses can also be used to assess how a participant’s visual attention can move across various aspects of a scene – from the TV, to their phone, and back again.

With this data, it’s possible to measure how many people actually saw a certain scene, and if they did, what exactly caught their eye. It’s also possible to see how long their attention was retained for, and at which point their attention began to dwindle. Using this data in combination can allow you to better predict what will gather attention, and to design a scene to best retain it.

This approach works regardless of whether you are trying to create a TV show that enthralls viewers, or if you just want viewers to notice the brand on screen. Of course, looking doesn’t mean liking, and this method works best when used alongside other methods that provide an understanding of the emotional response to the content.

GSR

Galvanic Skin Response (GSR, otherwise known as electrodermal activity or EDA), is a measure of physiological arousal detected by changes in the sweat glands of our skin. Moments of increased or decreased arousal will bring about proportional (if minute) changes in sweat gland activity.

Changes in sweat gland activity brings about small changes in the electrical conductance of the skin. By using electrodes typically attached to the fingers (although it is possible to measure from other areas of the body as well), these changes can be detected.

This allows investigators to collect and analyse data relevant to how exciting (or, on the other hand, boring) a scene may be. Applying this measure with knowledge of the context can be particularly informative – an exciting action movie would be expected to increase GSR activity, and if this doesn’t happen then new ideas about the media might need to be made.

Similarly, if showing an advert or product placement for a product that is intended to be relaxing, an increased level of GSR activity is unlikely to be the intention (although, as with anything, this depends on the aim of the content).

This is often measured by comparing the moments of peak arousal – when the GSR activity is significantly increased above baseline. A higher number of peaks is suggestive of increased arousal.

The weakness of this methodology is that while it can provide information about the level of physiological arousal, it doesn’t convey any meaning about the direction of the emotional experience (whether positive, negative, or neutral emotions are attached to the context – the valence).

The true power of this method comes into play when it’s combined with other measures that allow the attention, physiological arousal, and emotion to be triangulated and understood. By bringing more dimensions of data into media testing, more incisive and deeper insights can be made.

Facial expression analysis

It has become almost cliché to say that emotional connections are central to the success of any media content, but it is no less true. Research has shown that emotion facilitates the encoding and retrieval of memories [1], meaning that emotion is central to being remembered.

Increased emotional connections also increases the chance that the audience will engage with the media [2], ultimately meaning that the content that is more emotionally engaging will be more successful with the audience. Of course, in order to know how to improve the emotional engagement of the media, the emotional engagement must be measured.

Facial expression analysis presents the easiest and least-invasive method of measuring emotional expressions. By simply using a webcam, facial expressions can be recorded and analysed, providing information about the likelihood that a certain emotion is being exhibited.

Not all content elicits facial expression changes equally strongly. This method is particularly suited to comedy content, as that is more likely to reliably generate relevant facial expressions relating to joy and laughter (and if not, well, you have a problem). As ever, context is key when determining and testing hypotheses related to the effect of media.

EEG

While not as commonly used as the trifecta of methodologies above, electroencephalography (EEG) is increasingly employed to provide insight into the cognitive state of media viewers.

The method requires placing electrodes on the scalp, and recording the electrical activity generated by thousands of neurons (cells in the brain) signalling together. While this takes more time to set up with a participant, it can also be used alongside all of the other aforementioned methods to generate a level of understanding of the audience that is difficult to match.

Measures such as frontal asymmetry (in which activity from the front of the brain is compared across the left and right hemispheres) can also be used to indicate feelings of approach / avoidance [3], adding another layer of understanding to the media content.

While this method has to be used carefully under relatively stringent conditions, the method provides a direct line to cognitive processes.

Nonconscious responses

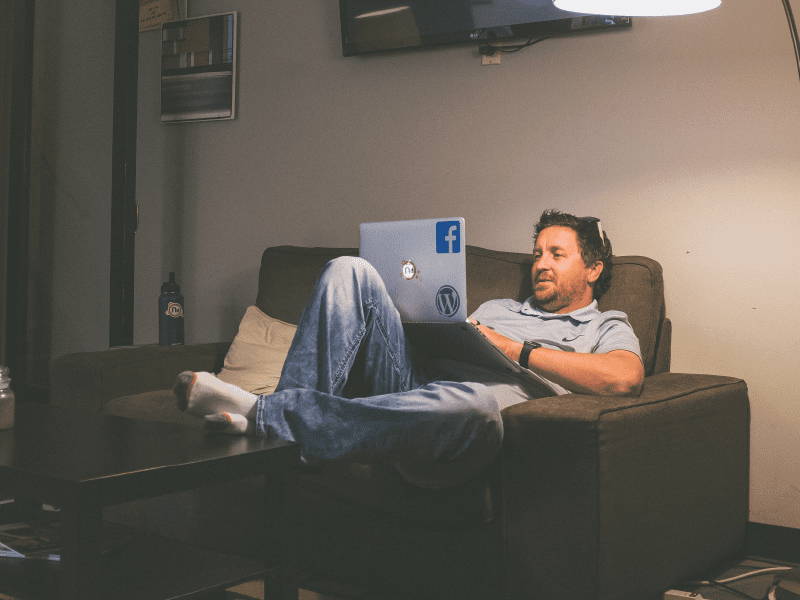

These methods allow insight into the audience response to media in a passive way. Asking media consumers what they thought of adverts during an ad break will often lead to a confused look – viewers don’t actively pay attention to every moment.

This is particularly crucial when it comes to dual-screen viewing (in which the viewer often uses or views media on their phone as well as on another screen). Due to the ease of which attention can be lost, gathering granular information about these events can allow media creators to better present, capture, and retain attention.

By using objective methods such as eye tracking, GSR, and facial expression analysis, data can be collected even without the conscious awareness of the participants. This means that data can be collected from those moments without the viewer having to make an explicit decision about their attitudes, thoughts, or feelings.

Furthermore, the nature of these methods means that data can be collected in naturalistic settings – with the participant sitting on the couch in front of the TV, if needs be. Being able to bring the methods as close to real life as possible means that the data will also reflect real life as much as possible.

It could be, for example, that less emotional expressions and / or lowered GSR activity precede a loss of attention (which could be captured by eye tracking data) – knowing when this happens can mean that the media is designed to cut earlier, or introduce new content, or change in some other way. The data can provide the insight, and this insight can help make the media better.

Making predictions about media

One of the crucial challenges for those working to gather new insights with media is how to predict the possibility of future success of an ad campaign or media content. While these methods aren’t a crystal ball to the future, being able to record vast amounts of data and looking into what about that data could be indicative of success is one way to get closer to such an understanding.

It could be that the number of joyful facial expressions correlate with the success of a comedy show, or a combination of increased physiological arousal, joyful facial expressions, and attention retained to the screen. Developing an understanding of which signals are of use is part of the experimental process, and allows for the generation of truly powerful insights.

Creating media is a complicated process, and success is never guaranteed. But in this highly competitive and saturated media market, companies need to do all they can to gain the advantage and remain top-of-mind to media consumers. The collection of unbiased insights shows the way forwards, and looks to be a new part of the ever-changing media landscape.

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading about the ways in which biosensors can complement existing methods to generate a deeper understanding of audience affect and engagement. To learn more about one of the central methods used in advanced media testing, download our free and comprehensive guide to GSR below.

Free 36-page EDA/GSR Guide

For Beginners and Intermediates

- Get a thorough understanding of all aspects

- Valuable GSR research insights

- Learn how to take your research to the next level

References

[1] Tyng, C. M., Amin, H. U., Saad, M. N., & Malik, A. S. (2017). The Influences of Emotion on Learning and Memory. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01454

[2] Teixeira, T., Wedel, M., & Pieters, R. (2012). Emotion-Induced Engagement in Internet Video Advertisements. Journal of Marketing Research, 49(2), 144-159. doi:10.1509/jmr.10.0207

[3] Rodrigues, J., Müller, M., Mühlberger, A., & Hewig, J. (2017). Mind the movement: Frontal asymmetry stands for behavioral motivation, bilateral frontal activation for behavior. Psychophysiology, 55(1). doi:10.1111/psyp.12908