Over the past decade, the use of neuroscience tools in market research has progressed from a “nice to have” add-on, to an essential part of any consumer research study. As we have detailed before on this blog, neuroscience tools are applied daily to a wide variety of use cases: Video advertising, driving and in-vehicle experiences, sensory evaluations, shopper experiences, and many more.

What all of these use cases have in common, however, is that they are all trying to achieve the same goal: To gain a better understanding of why humans behave the way that we do.

Today’s questions – such as being able to apply valid neuroscientific techniques to study how people respond to a virtual reality environment – did not just spring fully-formed into the research world, though. Instead, today’s questions have been built on decades of academic and industry research, which has provided the guard rails for what can (and cannot!) be validly measured in the moment from consumers.

Today, we will take a step back from the exciting consumer research being conducted in 2019, and look at some of the seminal research that has helped move the neuromarketing industry to where it is today. How can neuroscience predict what small-ticket consumer goods people will purchase? Are Super Bowl advertisers spending their ad dollars as efficiently as possible? Can neuroscience help researchers effect social change, like promoting smoking cessation and creating powerful female superhero role models? Read on!

- The Origins of Neuromarketing: The Somatic Marker Hypothesis

- Case study: In lab studies vs. in-market outcomes

- Case Study: Understand Sales of FMCG

- Case Study: Predicting Smoking Cessation Behavior

- Case study: The Importance of Female Superheros

- Case Study: Limits of Neuromarketing research

What is Neuromarketing?

Neuromarketing is an innovative field that merges neuroscience with marketing to understand and influence consumer behavior. By studying how the brain responds to marketing stimuli, companies aim to design products, advertisements, and marketing campaigns that are more effective and engaging.

At the core of neuromarketing is the belief that consumer decision-making is largely unconscious. Traditional marketing methods rely on self-reported data, such as surveys and focus groups, which can be unreliable due to biases and the limitations of self-awareness. Neuromarketing bypasses these issues by directly observing the brain’s responses.

Techniques used in neuromarketing include functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) and Electroencephalography (EEG). fMRI tracks blood flow in the brain to identify areas that become active in response to certain stimuli, while EEG monitors electrical patterns to understand emotional responses. Eye tracking and measuring changes in skin conductance are also used to gauge interest and arousal.

By analyzing this data, marketers can understand what captures attention, triggers emotions, and prompts purchasing decisions. For instance, neuromarketing can reveal how different colors, words, or product placement can impact a consumer’s subconscious perception and buying behavior.

However, neuromarketing also raises ethical concerns. Critics argue that it could lead to manipulation, exploiting subconscious triggers to drive consumer behavior without their awareness. As such, there is an ongoing debate about the ethical implications of using neuroscience in marketing.

In conclusion, neuromarketing represents a frontier in understanding consumer behavior, offering deeper insights than traditional marketing methods. While its potential is vast, it also necessitates careful consideration of ethical boundaries in its application.

The Origins of Neuromarketing: The Somatic Marker Hypothesis

Our review of seminal neuromarketing studies begins not with a neuromarketing study, but with a line of academic research. Previously in our blog, we have detailed the many ways in which various neuroscientific tools – electrodermal activity, electroencephalography, facial expressions, and so on – can be used to understand the human emotional experience.

No review of “important neuromarketing studies” would be complete, however, without a brief reflection on one of the most important academic hypotheses linking brain to behavior: the somatic marker hypothesis [1].

Antonio Damasio is a highly-influential neurologist and emotion neuroscientist, whose work with brain-injured patients helped identify the importance of brain-based processes in both the conscious and non-conscious components of decision-making. Damasio and his colleagues sought to understand why patients with damage to certain parts of their brains made decisions differently from healthy individuals, and published extensively on the link between electrodermal activity and choice.

Based on his work, Damasio posed the somatic marker hypothesis (SMH) as a way of explaining how the brain and body work in concert with one another to lead individuals towards the decisions they make.

In short, the SMH suggests that decision making is actually a learning process. When we make a decision, or a choice, and we experience the outcome, we will have some low-level (or even more overt!) emotional response to that outcome. That emotional response is manifested as some series of bodily reactions – an increase in skin sweat, a decrease in heart rate variability, an expression of emotion on our face – and information about that response is stored as a “somatic marker” (soma meaning “body”) in the brain.

When an individual later finds themselves in a similar situation, or making a similar choice, the relevant somatic markers are retrieved and provide information to help guide the decision process.

The SMH laid the groundwork for much of modern neuromarketing, by showing that we do not need to image consumers’ brains, using something like functional MRI, to understand when they something is getting an emotional response from them. Measures like electrodermal activity, although taken from the periphery of the body, can directly reflect processes in the brain that are related to decision making.

This provided earlier neuromarketers with a means by which they could non-invasively gain more insight into consumers’ behavior, and which could be done in a scalable fashion.

Neuromarketing research: In lab studies vs. in-market outcomes

One of the “holy grails” of neuromarketing is demonstrating that in-lab neuroscience measures relate, in some meaningful way, to a company’s key market outcomes. Neuromarketers are consistently tasked – as they should be – with providing validation that their measures are significantly related to consumer behavior.

The best of these validation studies are the ones in which the teams collecting and analyzing the data are blind to the in-market outcomes, ensuring that the research results are unbiased.

Check out: 5 Marketing Myths Disproved by Neuromarketing

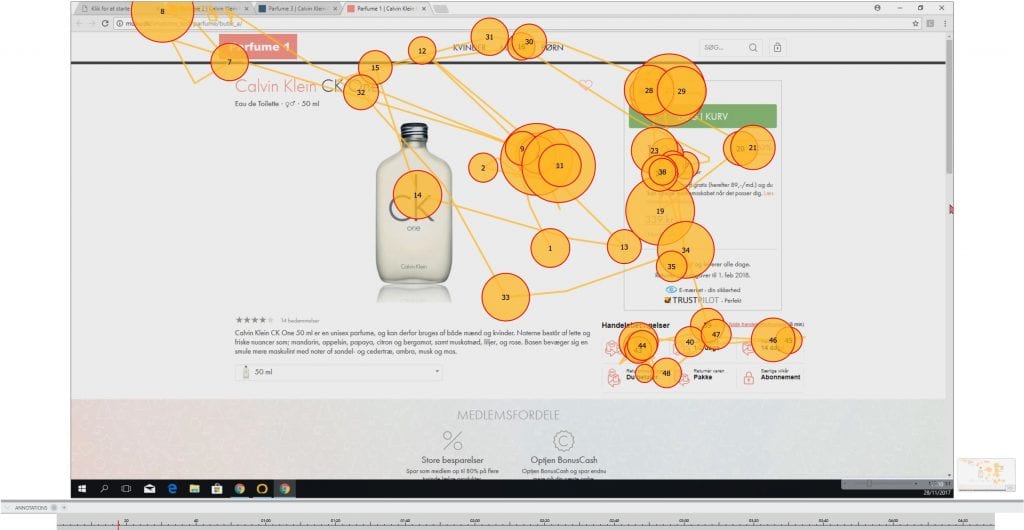

An excellent demonstration of this type of validation came in 2012, from Innerscope Research (now Nielsen Consumer Neuroscience). Innerscope was approached by Mimoco, a consumer electronics retailer, to test their “Mimobots” line of designer USB flash drives. These flash drives were designed to look like stylized characters, both pre-existing (e.g., Hello Kitty) and some entirely novel designs.

Mimoco had online sales data for hundreds of their designer flash drives, and provided Innerscope with a subset of about 30 of their top- and bottom-performing designs to test in the lab. Innerscope was blind to which designs had sold well, and which had sold poorly.

The designs were tested using a static, screen-based methodology in the lab, while EDA, heart rate, and eye tracking data were collected from respondents who were passively viewing the designs.

Innerscope then ranked the flash drives, from #1 to #30, based on data from the combination of biosensors. When Mimoco lined up Innerscope’s ranking with their own sales data, the neuroscience data correctly identified four of the top five sellers, and also correctly identified a number of the bottom-selling designs.

Overall, the in-lab results were able to explain 50% of the variability of in-market sales. Although there had been several studies prior to this one demonstrating relationships between neuromarketing techniques and in-market behavior, this was one of the most prominent single-blind studies to show that neuroscience tools can be used to reliably predict the sales of a high-volume consumer electronics product (while also highlighting the value of a biosensor-based research).

3 Popular Neuromarketing Studies

1. Case study: Sales of Fast-Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG)

Although the Mimoco study is remembered more for its design and results than its market impact, the next case study on our list made a much broader splash in 2016. In an ever-changing broadcast media landscape, CBS was looking to gain a deeper understanding into what made for effective television advertising.

As David Poltrack, the former Chief Research Officer at CBS, said, “With today’s consumer continuously exposed to more and more media messages, it is increasingly difficult for an advertiser to develop creative that breaks through and resonates with the target audience.”

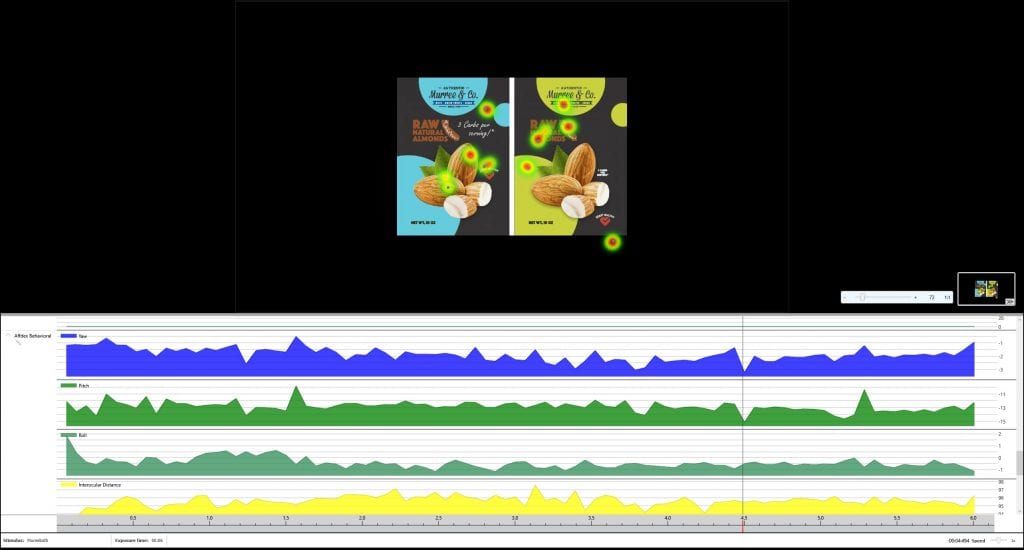

To this end, CBS partnered with Nielsen Consumer Neuroscience and Nielsen Catalina Solutions, to extend the concept of “neuroscience validation” to the broad category of fast-moving consumer goods. Nielsen Consumer Neuroscience tested 60 ads from a variety of FMCG categories (including food, household goods, beauty products, etc.). These ads were tested in Nielsen’s labs around the US, using a combination of EEG, EDA, and facial expression analysis.

Nielsen Catalina Solutions then provided data for each of those ads, using a combination of set-top box data and retail purchase data, to identify sales “lift” for households who were exposed to the advertisements versus not exposed. The researchers then looked at how well the in-lab neuroscience measures were able to predict which ads generated more sales lift in-market, and which ads didn’t move the needle.

The results demonstrated that not only were the neuroscientific measures able to significantly predict sales data for this large number of ads, but that – once again – a multimodal approach that incorporated all three measures (EEG, EDA, and FEA) was the best predictor of sales lift.

At a time when network broadcast companies were looking for new and better ways to make an emotional connection with their TV viewers, this large-scale validation partnership made a huge impact in the advertising research world.

2. Case Study: Predicting Smoking Cessation Behavior

One of the most heavily-cited studies in the neuromarketing field wasn’t actually a neuromarketing study at all; rather, it was a study showing how neuroscience could be used to identify more effective public service advertising.

Emily Falk, a neuroscientist at the University of Pennsylvania, wanted to understand the degree to which activity in the brain – specifically in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), which has been implicated heavily in decision-making processes – would predict call volume in response to the US National Cancer Institute’s anti-smoking campaigns [2].

Falk and her colleagues used functional MRI to test three TV ad campaigns promoting the USNCI’s 1-800-QUIT-NOW hotline, looking specifically at the degree to which each of the ads elicited activity in the vmPFC. They then compared the neuroimaging results to both self-reported ratings of “effectiveness” of the ads, as well as the call volume generated by each advertisement.

While there was no relationship between self-reported efficacy of the advertisements and called volume, vmPFC activity tracked directly with how many calls the 1-800-QUIT-NOW hotline received.

Although fMRI research is rarely conducted in the neuromarketing industry because of cost, logistics, and perceived invasiveness, the study nevertheless has been hugely influential with agencies that seek to promote better human behavior. The Ad Council, for example, frequently employs neuroscience testing to hone their public service advertisement creative – everything from ads for pet adoption to inspiring fathers to be more involved in their children’s lives.

3. Case study: The Importance of Female Superheros

Continuing on the topic of using neuroscience to affect positive change, iMotions recently partnered with Screen Engine/ASI, BBC America, and the Women’s Media Center to understand how various depictions of female superheroes are experienced by teenage males and females.

In the latest installment of BBC’s wildly-popular Dr. Who series, the main character was being portrayed by a woman for the first time in the show’s decades-long run. In addition to wanting to know how the “female Doctor” would be received by audiences, BBC, SE/ASI, and the WMC wanted to know how portrayals of superheroes – both male and female – impacted measures like self-esteem and self-confidence in younger demographics who looked to superheroes as role models.

The researchers tested a variety of TV trailers for programs anchored by superheroes like The Flash, Supergirl, Wonder Woman, and Luke Cage. An audience of late-adolescent males and females watched the trailers while the researchers measured their EDA, facial expressions, and visual attention (using eye tracking).

One of the key findings from the research was that young women responded much more favorably to depictions of female superheroes acting, well – like superheroes. Supergirl saving a plane from crashing, for example, resonated strongly with both female and male audiences. Conversely, the sexualization of female leads consistently led female viewers to tune out.

The use of neuroscience tools in this study revealed important guard rails around the most effective creative treatment of female superheroes. The researchers hope that this investigation will help generate change in the approach to storytelling in TVs and movies, and that the increased prevalence of female superheroes will continue to provide role models to a younger generation of female viewers.

Limits of Neuromarketing research

Of course, not all of neuromarketing’s history is paved with sales validation, smoking cessation, and promotion of gender equality in media. A handful of the best-known neuromarketing studies are famous for their infamy. These studies have nonetheless added great value to the field, by educating both neuromarketing consumers and providers about what these types of tools cannot do.

One highly-visible study was published as part of a New York Times op-ed in the fall of 2011. Martin Lindstrom describes a functional MRI study that he had conducted in collaboration with the now-defunct MindSign Neuromarketing. Respondents in the study were placed in an MRI scanner and exposed to ringing iPhones, and the researchers noted activation of (among other regions) the insular cortex in the brain.

Briefly, the insula is a “jack of all trades” region of the brain that is implicated in a wide variety of cognitive processes, including emotion processing, sensory integration, experiential consciousness, and many others [3]. Lindstorm picked just one of those functions – the experience of “love and compassion” – and concluded that respondents felt the same kind of love for their iPhone as they do for family or other loved ones.

Drawing that type of after-the-fact conclusion is similar to saying, “My new coworker is wearing sneakers today, so they must be a marathon runner”. Sure, that could be! But people also wear sneakers because they’re comfortable, or because they have a long walk to the office in the morning, or because they like the way they look, or any number of other reasons.

This is called “reverse inference” – finding a result, and cherry-picking an explanation for it after the fact, rather than coming up with a real hypothesis first – and Lindstorm’s assertion did not go unnoticed. A group of more than 40 academic neuroscience researchers co-authored a response letter to the New York Times, highlighting the lack of scientific validity of the claim.

Over the years, there have been similar, highly-visible examples of neuromarketing “gone wrong”. These serve as important cautionary tales for research consumers and providers alike: Neuromarketing must, above all else, be credible to be valuable, and an educated market is one that won’t let bad research slide. In a rapidly-growing industry, keeping these studies in mind is critical for holding everyone accountable for doing the best research they possibly can.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the ethical issues of neuromarketing research?

Neuromarketing research raises several ethical concerns. One of the primary issues is the potential for manipulation. By understanding and targeting the subconscious drivers of consumer behavior, there is a risk of manipulating customers without their conscious consent. This raises questions about consumer autonomy and the ethics of influencing decision-making at a subconscious level.

Another concern is privacy. Neuromarketing involves collecting sensitive data about an individual’s preferences and brain activity, which could potentially be misused if not properly safeguarded. The confidentiality and use of this data is a significant ethical consideration.

Finally, there’s the issue of fairness. The use of neuromarketing techniques might create an uneven playing field, where companies with access to these advanced tools have an undue advantage over competitors and consumers, potentially leading to market distortions.

What are the problems with neuromarketing?

Apart from ethical concerns, neuromarketing faces several practical and scientific challenges. The reliability of neuromarketing methods is a significant issue. Brain imaging and measurement techniques can vary in their accuracy and may not always provide consistent results. The interpretation of neurological data can be complex and subjective, leading to potential inaccuracies in understanding consumer behavior.

Putting it All Together

The neuromarketing industry has come a long way in the last 15 years. There has been more groundbreaking research done than we have space to share here, and there have been some stark examples of “how not to do neuromarketing”, as well. We hope that this overview of a few seminal studies has been interesting, and if you’d like to learn more, be sure to keep an eye on our blog for more exceptional case studies in the future!

References:

[1] Damasio, A. R. (1996). The somatic marker hypothesis and the possible functions of the prefrontal cortex. Philos Trans R Soc Lond [Biol] 351:1413–1420.

[2] Falk, E. B., Berkman, E. T., Mann, T., Harrison, B., & Lieberman, M. D. (2010). Predicting persuasion-induced behavior change from the brain. The Journal of Neuroscience, 30, 8421–8424.

[3] Gasquoine PG (2014). Contributions of the insula to cognition and emotion. Neuropsychol Rev 24: 77–87.