Renowned photographer and author Michael Freeman reached out to iMotions to do a collaboration on eye tracking in photo compositions.

People might think of still images as fairly boring compared to videos, websites, and especially glitzier forms of media like VR. Because still images are not dynamic, changing, or immersive stimuli like videos, they tend not to elicit comparably strong reactions in either facial expressions or skin conductance.

But don’t be so quick to disparage the humble still image. Although the medium is not dynamic, the way in which we perceive it is – yes, we might perceive the image in its entirety in our minds in an instant, but if you watch someone looking at a photograph, their eyes are moving all over the place. The progression of the gaze in how we attend to objects and elements, the order in which we attend to them, and for how long – all of these things contribute to our subjective experience when we are looking at that photograph.

To direct the gaze, and thereby direct the experience of a medium, depends very much on an implicit knowledge of composition. In videos, you can direct attention by moving objects into frame, using dialogue, dynamically changing the focus of the camera, or cutting to a different scene. It’s relatively easy to direct the observer’s gaze with each cut. With still images, because there is no temporal element to it, you have to manipulate variables like contrast, color, grouping, and placement, and hope that the observer’s eyes do what you want them to.

On a crisp fall mid-pandemic day, a photographer named Michael Freeman reached out to iMotions with an idea for his latest book. Michael is a renowned and prolific author on photography and is most famous for The Photographer’s Eye, which has been sold in over 30 languages. In his latest work, On Composition, Michael sought to provide a literary masterclass on how to think about and apply principles of composition to photography. What would set this book apart from the others was the use of eye tracking technology, to determine empirically how peoples’ search behavior correlated with the intention of the artist.

Not one to turn down a fun project, I created an iMotions study with several of Michael’s photographs and showed them to some of my colleagues in a controlled setting with a 60-Hz Smart Eye Aurora.

The destination might be the same but the journey might be different

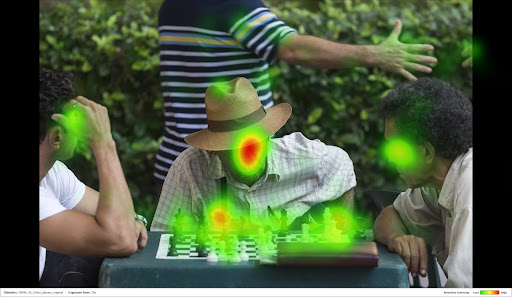

One of Michael’s examples was a photo he took in Cartagena, Colombia, of people playing chess in a park. In this composition, Michael was drawn most to the man in the center with the hat, and the two people on either side providing a kind of symmetry. In the background, another man extending his hand provided another dynamic focal point in the background.

Here is the heatmap of aggregated gaze data for that photograph:

And here is that same photo but with two respondent’s gaze data overtop:

As Michael looked at the heatmap, he found that people attended most to what he wanted to focus on – the central man’s face, and the men on either side. Certainly, we always have a tendency to attend more to faces in an image. But he was surprised at the amount of attention people paid to the chessboard, and how little people attended to the hand in the background – differences between what he focused on as the photographer that were not consistent with what observers looked at. What was more surprising were the individual differences between participants in what they focused on first, and in what order they subsequently jumped to between each individual, the chess pieces, the man in the background, and his hand. The first respondent had a boxy progression of gaze as he went around in a circle clockwise. The second respondent had a more plus-shaped progression that always went back to the central man’s face before moving to something else. Perhaps this variability in how each individual moves from one element to the next is a byproduct of its symmetrical design; there is no one clear ‘direction’ that moves the gaze along an established path.

Using salience to direct an observer’s experience

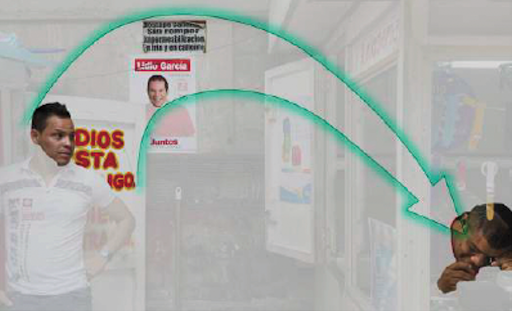

In another photograph, Michael wanted to make a “busy” image with many interesting elements, but none of them central.

For this photograph, he had a specific intent for observers to look first at the man on the left, and then to follow the signage and text up and around, eventually, only later on, settling on the watch repairer at the bottom right.

The heatmap of the photograph showed that all of the elements were attended to appropriately, with even a few bonuses (extra attention being paid to the black and white text up top, and the man’s cellphone):

But heatmaps are not good for looking at the temporal progression of attention over time. This was best accomplished using our “Grid AOI” feature, which allows you to break an image up into sections of a predetermined size, and calculate metrics like Time to First Fixation. The numbers here indicate ranking of the AOI, from earliest TTFF to latest:

Using our Grid AOIs to aggregate eye tracking data, we see through the TTFF metric that people on average tended to look first at the man, then up at the signs, and eventually to the watch repairer on the right – just as the artist intended.

Another way we can look at the temporal progression through AOIs is by using our Transition Matrix export, which is a powerful tool for calculating the “intuitive flow” of an image by calculating how often people move their eyes from one specific AOI to the next. For the first photo of the men playing chess, the Transition Matrix would have been pretty equal across AOIs, as people attended to the different features in various orders. For this photograph, since there was a predetermined “guiding” of the eye through placement of various salient features that was consistent across respondents, we would expect the Transition Matrix to reflect a disproportionate number of transitions from AOIs 1 to 2, 2 to 3 or 4, 5 to 6, and so on.

This is just a sample of some of the very cool conclusions Michael found in our brief adventure with eye tracking in the world of professional photography, which are published in his latest book. Although eye tracking was solely used in this study, the multimodal approach can certainly still be used for still images, especially using EEG. It would have been extremely interesting to measure not only observers’ visual experiences perceiving the photographs, but also their intrinsic attraction or avoidance that they feel towards the pictures. Art is extremely intuitive and personal, and some might balk at using scientific tools that might threaten to ‘dehumanize’ the experience of art. But we have been seeing a delightful trend lately toward the use of scientific tools in design (check out our blog on Neuroarchitecture and our latest Community Masterclass with architect Ann Sussman). I had a blast with this study, and gained a new appreciation for the skills required to make a good photo. And for Michael and the world of photography, the use of eye tracking has provided an unprecedented new dimension to the experience of these photographs – especially for the artist behind them.

To purchase a copy of On Composition, check out this link on Amazon.

Eye Tracking

The Complete Pocket Guide

- 32 pages of comprehensive eye tracking material

- Valuable eye tracking research insights (with examples)

- Learn how to take your research to the next level