Human emotions are complex, with experts debating their exact number. Theories like Ekman’s six basic emotions, Plutchik’s Wheel, and dimensional models explore emotional expressions, cultural variations, and physiological responses. Emotions manifest through body, mind, and behavior, shaping experiences, decisions, and social interactions universally yet uniquely.

Table of Contents

What Are Our Core Emotions?

Emotions are fundamental to the human experience, but experts differ on exactly how many emotions exist. Some theories focus on a small set of core emotions, while others recognize dozens of distinct emotional states. Regardless of the total number, most frameworks agree that a handful of basic emotions are shared by all humans and have recognizable expressions across cultures.

These core emotions trigger coordinated changes in our minds and bodies- from physiological reactions (like heart rate or hormones) to psychological feelings and behavioral expressions. In this article, we’ll explore major psychological models of emotion, including Paul Ekman’s basic emotions, Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions, and dimensional models, and discuss how these emotions are universally recognized yet expressed with individual and cultural variation. We will also describe how core emotions manifest in terms of bodily responses, subjective experience, and behavior.

Paul Ekman’s Basic Emotions (Discrete Emotion Theory)

One influential framework comes from psychologist Paul Ekman, who identified a set of basic emotions based on cross-cultural studies of facial expressions. Ekman originally proposed six universal emotions: anger, surprise, disgust, enjoyment (happiness), fear, and sadness.

These emotions emerged consistently in research-for example, people from very different cultures could reliably identify these feelings from photos of facial expressions. Ekman’s classic studies in the 1960s and 1970s (including work with remote tribes in New Guinea) demonstrated that these six facial expressions are universally recognized across all human groups.

Each basic emotion is associated with a distinct facial expression (happiness with a smile, surprise with raised eyebrows, fear with widened eyes, etc.) and tends to be triggered by certain kinds of events or stimuli. Ekman later found evidence for a seventh basic emotion, contempt, which also showed a unique facial expression.

Ekman’s basic emotions are believed to be hard-wired and evolutionarily adaptive. For instance, fear helps us respond to threats (with a characteristic “fear face” of wide eyes and open mouth that might enhance sensory intake), while disgust (with a wrinkled nose) helps expel or avoid harmful substances.

Anger prepares us to confront obstacles, and sadness may elicit social support. Importantly, Ekman noted that while these core emotions are innate, cultural “display rules” influence how and when people outwardly express them. For example, in some cultures people may suppress anger in public, or avoid showing sadness to strangers.

Still, the underlying facial patterns for these emotions are universal, even if we learn to modulate our expressions. So, in summary, Ekman’s theory suggests a small number of basic emotion categories that each have distinct expressions and are recognized worldwide, providing a biological foundation for human emotions.

Key Indicators for Ekman’s Six Core Emotions

This markdown format outlines Ekman’s six core emotions and some key facial markers or manifestations associated with each. These markers are often described in terms of the Facial Action Coding System (FACS), although the table below is simplified for clarity.

| Emotion | Facial Manifestations (Key Indicators) |

| Anger | – Brows lowered and drawn together (corrugator supercilii muscle) – Tensing or tightening of the lower eyelids – Lips pressed firmly or slightly parted in a squared shape – Nostrils may flare, jaw may clench |

| Disgust | – Nose wrinkling or “crinkling” of the upper nose area – Upper lip raised, sometimes showing upper teeth – Lower lip may protrude slightly – Cheeks raised and slight squint around eyes |

| Fear | – Brows raised and drawn together, creating wrinkles in the center of the forehead – Upper eyelids raised, eyes wide open (exposing more sclera) – Lips slightly parted or corners pulled back in a grimace – Tense lower eyelids (sometimes producing a slight “fear grimace”) |

| Happiness (Joy) | – Corners of the mouth drawn back and up in a smile – Cheeks raised, causing slight wrinkling (“crow’s feet”) around the outer corners of the eyes – Lower eyelids may be relaxed – A genuine (Duchenne) smile involves both the zygomatic major and orbicularis oculi muscles |

| Sadness | – Inner corners of the eyebrows raised (frontalis, inner part) – Eyelids may appear droopy or slightly closed – Corners of the mouth pulled down – Nasolabial folds often more pronounced, and the face may look “long” or heavy |

| Surprise | – Brows raised high, creating horizontal forehead wrinkles – Eyes wide open (upper eyelid elevated, lower eyelid relaxed) – Jaw drops open slightly (mouth agape) – Expression is typically brief before transitioning to another emotion |

Note:

- The exact muscle movements can vary by individual and context, but these features are commonly associated with each basic emotion.

- Duchenne smiles (associated with genuine happiness) engage both the mouth (zygomatic major) and the eyes (orbicularis oculi), whereas a non-Duchenne (sometimes “polite”) smile may only engage the mouth.

- Ekman later added Contempt to his list of basic emotions; however, many classic references still focus on these six.

Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions (Psychoevolutionary Model)

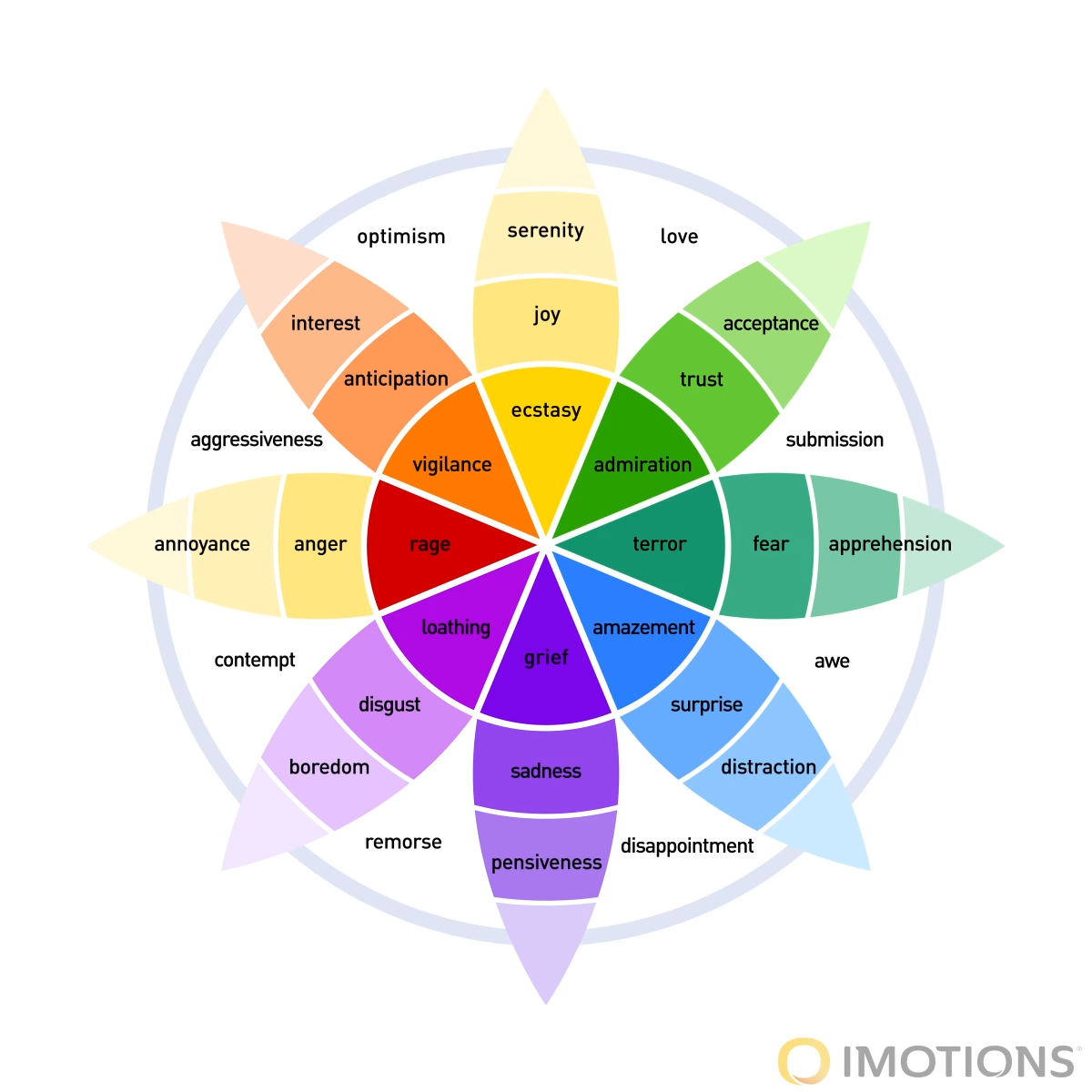

Another prominent model was proposed by psychologist Robert Plutchik, who suggested eight primary emotions arranged as opposites on a color wheel. Plutchik’s core emotions are joy, trust, fear, surprise, sadness, disgust, anger, and anticipation-essentially a set of eight basic feelings that combine to form more complex emotions. Each emotion has an opposite (joy vs. sadness, trust vs. disgust, fear vs. anger, and surprise vs. anticipation), and Plutchik depicted them in a circular diagram often called the Wheel of Emotions. The wheel format illustrates how emotions can mix and vary in intensity.

Plutchik’s framework is psychoevolutionary, meaning it ties each emotion to adaptive behavior from an evolutionary standpoint. For example, fear corresponds to the urge to escape (flight), anger to the urge to fight, trust/acceptance to affiliation, and disgust to rejection (spitting something out).

The Wheel of Emotions not only categorizes eight basics but also shows how they interact. Emotions adjacent on the wheel can merge into new feelings (Plutchik termed these combinations dyads). For instance, joy + trust = love (a primary dyad), and sadness + disgust = remorse. Emotions directly across from each other are opposites that do not mix (e.g., anger is the opposite of fear, so there is no blend of anger and fear on the wheel).

Plutchik also emphasized intensity: each primary emotion can manifest in varying strength. A mild version of anger might be annoyance, while an extreme version is rage. Likewise, serenity → joy → ecstasy represent increasing levels of happiness. By accounting for combinations and intensities, Plutchik’s model expands the number of distinguishable emotions far beyond eight- in fact, he described 24 “dyads” (two-emotion blends) and even larger combinations, illustrating the rich spectrum of human feelings.

Plutchik’s Wheel provides a vivid way to visualize emotions: a color wheel of feelings where basic emotions are the primary colors. It underscores that while we have a set of core emotions, our actual emotional life is complex and nuanced-much like colors blend to create new shades, our basic emotions mix to form the myriad emotions we experience.

Dimensional Models of Emotion (Circumplex Model)

Not all psychologists classify emotions as discrete categories; another approach is to describe emotions along continuous dimensions. Dimensional models argue that what we call specific “emotions” are points in a broader emotional space.

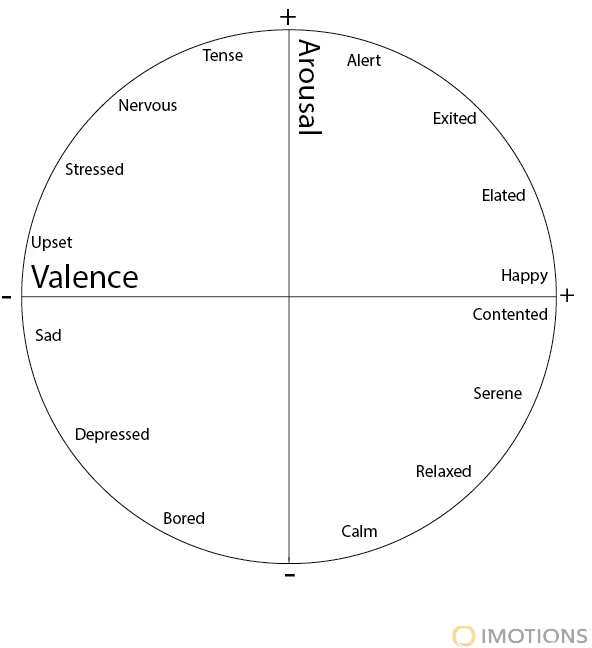

A well-known example is Russell’s Circumplex Model of Affect, which plots emotions in a two-dimensional circle defined by: (1) Valence- how positive or negative the emotion is, and (2) Arousal- the level of physiological activation or intensity (high vs. low). In this view, emotions are not totally separate islands, but gradients on a map.

For instance, happy and content are both positive in valence, but happy is higher arousal (more energetic) while content is lower arousal (more calm). Fear and anger both have negative valence and high arousal (a frightened person and an enraged person are both highly activated, though with different flavor), whereas sadness has negative valence but often low arousal (down, low-energy). Emotions like excitement (high arousal, positive) or boredom (low arousal, negative) find their place in other quadrants of this two-axis space.

Under a dimensional view, there isn’t a fixed number of “basic” emotions-instead, there is a continuum of emotional states. For example, “anxiety” might be a moderate-arousal, moderately unpleasant state, halfway between calm and fear. “Delight” might be very pleasant and fairly aroused, near joy but with a touch of surprise. Because dimensions are continuous, one can theoretically map an infinite variety of emotion shades.

That said, dimensional theorists acknowledge that our language uses discrete labels, and certain regions of the map correspond to the familiar basic emotions (e.g., a cluster around high-arousal-negative could correspond to anger/fear, etc.).

Some models add a third dimension such as Dominance/Control (as in the PAD model: Pleasure, Arousal, Dominance), which accounts for the sense of control vs. submissiveness one feels during the emotion. For instance, anger and fear are both negative-high arousal, but anger is higher in dominance (feeling in control or aggressive) whereas fear is low in dominance (feeling controlled by circumstances).

Overall, dimensional models highlight that emotions are interrelated and lie on a continuum, rather than being completely separate islands. They are especially useful for showing gradients and mixtures of feeling (for example, halfway states like bittersweet or anxious excitement).

This complements the categorical approaches of Ekman and Plutchik by providing a different lens: instead of asking “which basic emotion is this?”, the dimensional approach asks “where in the space between valence and arousal is this emotion?”. Both perspectives help us understand the rich tapestry of human emotions.

Universal Emotions and Cultural Variation

While different models define emotions in various ways, they all recognize a set of core emotions that appear to be universal. Research strongly supports the idea that certain emotions (and their expressions) are shared by all humans. As noted above, Ekman’s six (or seven) basic emotions have distinct facial expressions recognized across cultures. Even people from isolated societies with no exposure to Western media could identify expressions of happiness, anger, fear, etc., and produce similar expressions in appropriate contexts.

This suggests a biological basis: these fundamental emotions were shaped by evolution and thus appear in every human population. In fact, psychologists often refer to them as “universal emotions.” Each of these universal emotions is thought to have distinctive physiological signatures and expressive behaviors that serve adaptive functions (for example, fear’s wide-eyed gaze enhances vigilance, disgust’s grimace reduces inhalation of offensive substances).

However, saying emotions are universal does not mean they are experienced or displayed in exactly the same way by everyone. There is considerable cultural and individual variation in emotional expression. All humans feel anger, joy, sadness, and so on, but how we express or regulate these feelings can differ widely. The aforementioned Paul Ekman also introduced the concept of cultural display rules- socially learned rules about showing emotions. Different cultures have norms about which emotions are appropriate to express openly, to whom, and in what context.

For example, in Japan it’s common to mask negative feelings in public to preserve group harmony, whereas in some Mediterranean or Latin cultures, open expression of both joy and anger may be more acceptable. The intensity and outward expression of emotions can vary from person to person and culture to culture. One culture might encourage stoicism (downplaying expressions of pain or sadness), while another encourages emotional expressiveness as a sign of sincerity. These variations are superficial differences in expression, not in the underlying ability to feel the emotion- the core emotional capacity is human-universal, but its presentation is shaped by social context.

Besides culture, other factors like gender roles and individual temperament influence emotional expression. For instance, men in some societies might be conditioned to suppress tears (sadness) due to gender norms, whereas women might face stigma for expressing anger. Despite these differences, studies find that when genuinely felt, the facial muscle movements for basic emotions are very similar across groups- suggesting that at a biological level, we all speak the same “emotional language” through facial expressions, even if we sometimes hide or modify those expressions. In short, core emotions are well-defined and universally recognized in terms of facial and physiological patterns, but there is endless variety in how people interpret, value, and express those emotions in daily life.

How Emotions Manifest: Body, Mind, and Behavior

Emotion is not just a feeling; it is a whole-body experience. Psychologists commonly describe three components of emotion:

- Physiological Responses: Emotions spark immediate changes in our body’s physiology (autonomic nervous system activity, hormones, etc.). For example, heart rate and blood pressure may rise with anger or fear, driven by adrenaline and the “fight or flight” response. Fear can produce butterflies in the stomach, a pounding heart, and sweating, mobilizing energy for escape. Anger often causes muscle tension, a flushed face, and a rush of blood to the hands (preparing for combat). Sadness can have the opposite effect on arousal, with low energy or tears. Joy or happiness might cause a release of dopamine and endorphins, leading to a warm, relaxed feeling or energetic excitement. Even subtle emotions have bodily correlates-anxiety might cause jitters, disgust can trigger nausea or a gag reflex, etc.

- Subjective Psychological Experience: This is the “feeling” aspect of emotion-how it is experienced in the mind. Each core emotion has a recognizable subjective flavor: anger feels “hot” and tense, fear feels ominous, sadness feels heavy and depleting, joy feels light or euphoric. These feelings are informed by appraisal (our interpretation of the situation). For instance, two people might see a surprise test and respond differently- one feels anxious (it’s a threat), the other excited (it’s a challenge). Complex emotions like pride or guilt also involve higher-level cognitive evaluations (e.g., personal standards or social context). Ultimately, the subjective component is what we label as “I am angry” or “I am happy.”

- Behavioral Expressions (and Action Tendencies): Emotions manifest externally through expressive behavior (facial expressions, vocal changes, gestures, posture) and action tendencies (urges to act). Fear can provoke an impulse to flee, anger motivates confrontation, sadness may prompt withdrawal or seeking comfort, and joy may encourage approach and social bonding. These behavioral changes often have evolutionary roots (fear enhances survival by urging escape; anger protects resources by confronting threats). Emotional expressions also serve a social communication function- a scream of fear alerts others to danger; a smile invites social contact.

These three facets-physiology, psychology, and behavior-work together as an integrated response whenever we experience an emotion. Take fear as an example: if you encounter a growling dog, you might feel an intense wave of fear (subjective feeling of danger), your body might freeze and your heart rate skyrockets (physiological arousal), and you might find yourself backing away (behavioral response). All of this can happen within seconds, without any conscious effort. Emotions are essentially coordinated packages of responses that help us deal with the situation at hand.

It’s also worth noting that emotions are typically brief episodes (seconds or minutes) rather than long-lasting moods. If a feeling persists for a very long time, it might be more accurately considered a mood or disorder. But during those emotional moments, their effects on body, mind, and behavior can be quite powerful.

Conclusion

Emotions are a complex, rich aspect of being human. Psychologists have proposed various ways to categorize and explain them- from a small set of basic emotions we all share, to elaborate wheels and dimensional maps capturing the nuances of feeling. How many emotions exist? The answer depends on how we define “emotion.”

If we focus on universal categories, there are only a handful (ranging from Ekman’s six or seven, to Plutchik’s eight). If we consider all the subtle varieties and blends, there may be dozens upon dozens. What remains constant across these models is that some core emotions are common to everyone and can be recognized through similar facial expressions and physiological patterns worldwide.

Despite differences in culture, language, or personality, a smile of happiness or a cry of pain are broadly understood signals- a testament to our shared emotional heritage. At the same time, each person’s emotional life is unique. Culture, upbringing, and context shape how we feel and express our emotions, leading to a diversity in emotional expression.

Understanding frameworks like Ekman’s, Plutchik’s, or the circumplex model can help us make sense of our feelings- recognizing, for example, that anger and fear might be different flavors of a high-arousal state, or that what we call “love” might be a blend of simpler joys and trusts.

In practical terms, knowing that emotions involve intertwined physical, mental, and behavioral responses can also empower us. We might use body signals as clues to what we’re feeling, or practice changing our behavior as a way to influence our emotions (like taking deep breaths to calm down fear).

Emotions are often brief, but their impact is profound: they color our memories, drive our decisions, and connect us to others. By appreciating both the universal core of emotions and the ways they manifest differently for each of us, we gain a deeper understanding of ourselves and others. Emotions are at once universal and personal- universally human in their biological foundations, yet personally shaped in how they emerge and unfold day to day.

References

- Ekman, P. Emotions Revealed: Recognizing Faces and Feelings to Improve Communication and Emotional Life. New York: Times Books; 2003.

- Ekman, P., Friesen, W. Constants across cultures in the face and emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1971; 17(2): 124–129.

- Plutchik, R. The Emotions: Facts, Theories, and a New Model. New York: Random House; 1980.

- Russell, J.A. A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1980; 39(6): 1161–1178.

- Mehrabian, A. Framework for a comprehensive description and measurement of emotional states. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 1995; 121(3): 339-361.

- Matsumoto, D. Cultural influences on research methods and statistics. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 2002.

- Scherer, K.R. Emotion as a multi-component process: A model and some cross-cultural data. Review of Personality and Social Psychology, 1984; 5: 37–63.

Free 52-page Human Behavior Guide

For Beginners and Intermediates

- Get accessible and comprehensive walkthrough

- Valuable human behavior research insight

- Learn how to take your research to the next level