Have you ever wondered why certain places feel instantly warm and inviting, while others feel bleak? For Hernan Rosas, it became a lifelong fascination that fueled his unique path in design. A path that has led him to earn a degree in architecture, publish several studies on human interactions with the man-made world, and now to design his own curriculum at the University of Maryland and shape how tomorrow’s design can be better for humanity.

Growing up in San Jose, California, with a family from Mexico, Rosas felt a stark contrast between his two environments. “I’ve always gone to where it feels nice,” Rosas reflected. The urban design of San Jose never quite resonated with him, while visits to Mexico offered a sense of safety and comfort. This sparked his curiosity – how could the physical environment have such a profound impact on our emotions?

This early interest in how physical environments influence feelings and perceptions led him down a path of exploration and discovery. Rosas pursued a master’s degree from the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Architecture, complementing it with a background in cognitive psychology from UC Berkeley. His goal was to bring a human-centric approach to design and architecture – fields that often rely more on intuition than rigorous data.

Central to reaching this goal was Rosas’ time with theHAPI.org (the Human Architecture and Planning institute), an organization dedicated to integrating human data into design.

“I wanted to get the experience of actually doing what I think it is that architects need to do, which is to go back and look at the human data and see how we actually respond to the environment.”

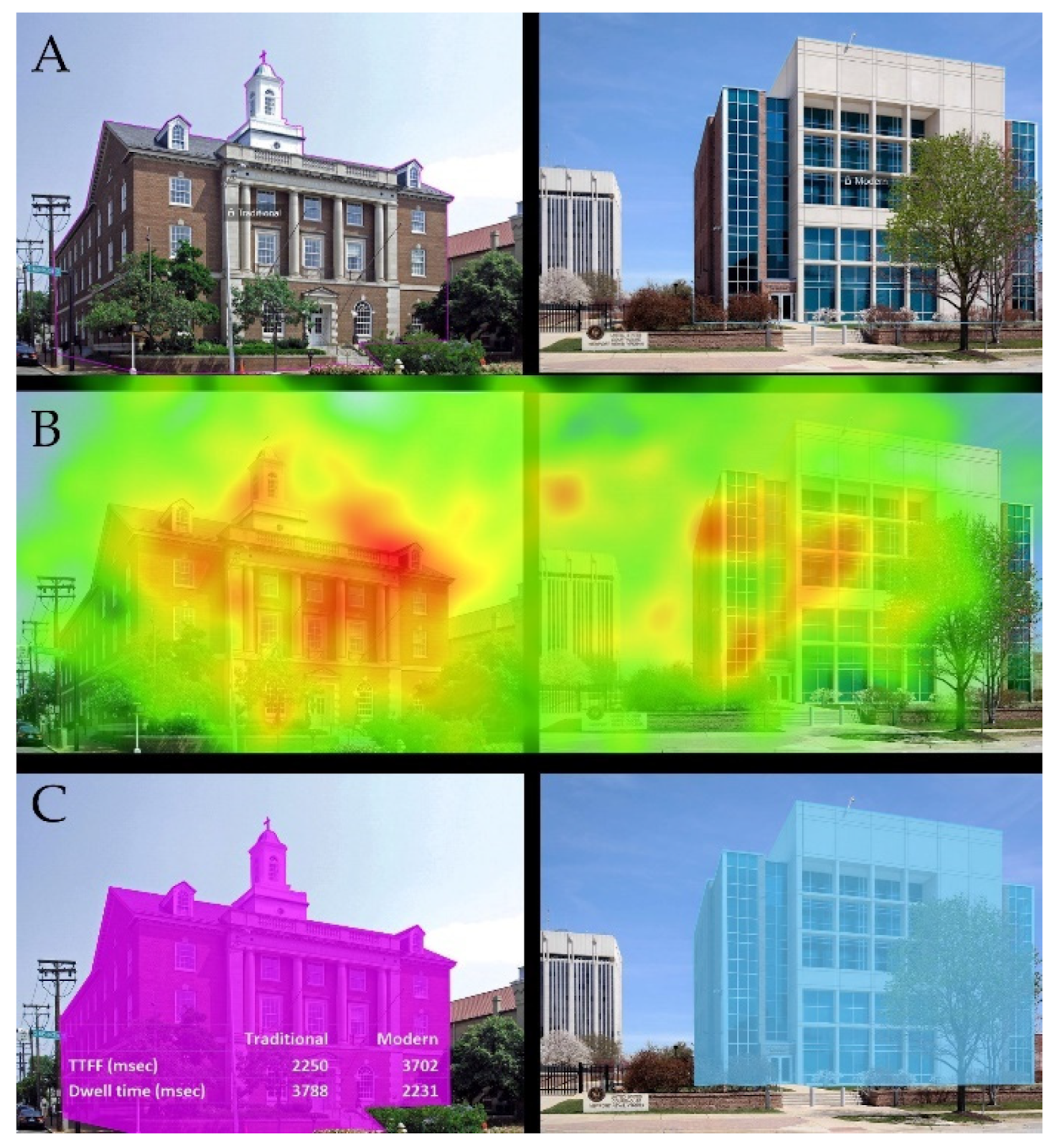

Under the mentorship of theHAPI.org’s President and cognitive architect, Ann Susmann, Rosas led several research studies to gain a deeper understanding behind survey results from the National Civic Art Society, which found a 72% preference for traditional over modern design in U.S. federal buildings. “We wanted to know what was going on behind those survey results, so we used iMotions to create a study with those exact same images that people had already been polled on, and we put them to the test.”

Through online eye-tracking studies, Rosas and his team found that buildings with a certain type of organized complexity, such as that found in nature and pre-modern architecture, attracted participants’ gaze faster and held it significantly longer compared to images lacking those features. Looking at these non-conscious responses provided deeper insight behind the preference for certain designs.

(A) At left, the traditional Martin V. B. Bostetter Jr. U.S. Courthouse in Alexandria, Virginia, paired with a modern counterpart, the U.S. Courthouse, in Newport, Virginia. (B) Heatmaps of both buildings (C) Outlined AOI. The TTFF was shorter for the traditional building and the dwell time longer.

With the credibility of seven biometric studies forming the basis for his design approach, Rosas used his research to bolster his PhD applications, eventually landing him at the University of Maryland, where he is now developing the Department of Architecture’s first class that combines theoretical knowledge with hands-on experience in using biometric data in design.

“There are very few courses like this,” said Rosas. “The education system, in terms of architecture and design, is not built to incorporate human response data yet. There’s a lot of data missing, and I’m excited to teach students about this kind of data that they can then take into the field.”

That’s why Rosas says these courses are so important. While some have been early to adopt, most of the industry has moved slowly. Many design firms experience resource, access and expertise challenges that keep them from being able to utilize human behavior data.

“These experiences and tools allow aspiring designers and architects to learn biometric research and apply it to their craft. It’s planting the seed for new and innovative approaches within the industry, giving credibility to research-backed design rather than relying solely on intuition. Human data will be available for people to use in designing spaces based on how we actually perceive the world.”

Beyond academics, iMotions has provided Rosas with the answers he’s been seeking since childhood. “It explains some of the effects I felt as a child,” Rosas shared. “It explains why certain enclosures where my grandparents in Mexico lived felt better and safer, and why the places where I grew up didn’t. Mexico has better textures; San Jose lacks a lot of that.”

Rosas’ story is a testament to the power of curiosity and the transformative potential of tools like iMotions. It reminds us that the greatest impact comes from building a comprehensive understanding of human behavior, often needing to uncover insights that cannot be seen or consciously conveyed.

“If I hadn’t gotten a hold of iMotions, I would’ve continued designing boring buildings,” he said “I’m thankful to have the chance to uncover this information. While I like to design, I prefer to be a discoverer of data.“

Eye Tracking

The Complete Pocket Guide

- 32 pages of comprehensive eye tracking material

- Valuable eye tracking research insights (with examples)

- Learn how to take your research to the next level