Heuristics are mental tools that help us navigate our lives – they are shortcuts for perceptions, allowing us to quickly understand information that we are presented with. They are powerful and essential. They also lead us astray all the time.

Let’s say I toss a coin six times and write down the result each time (with “H” for “heads” and “T” for “tails”). Which sequence do you believe is more likely to occur? H-H-H-T-T-T, or H-T-T-H-T-H?

Most people when given this question choose the latter option, however, the answer is that both are equally likely to appear. We simply use a heuristic – a shortcut – of what appears “more random” and apply that to the question [1]. While this approach is quick, and usually helps us make correct enough decisions most of the time, the very speed of this process can cause inaccuracies. Sometimes solutions take time to reach.

This can be seen in scenarios more complex and realistic than simple coin tosses. If I was to describe a randomly selected person as “introverted with a need for order and structure”, would you think they are more likely to be a librarian or a farmer? Our gut instinct often answers with the former – these are characteristics that we usually associate with librarians. However, when you consider the number of librarians vs. the number of farmers (and considering they are “randomly selected”), the answer is actually more likely to be the latter [2]. Heuristics can shape even seemingly complex judgments.

Heuristics as a concept was first established by the work of Nobel prize-winning psychologists, Daniel Kahnemann and Amos Tversky (from whom both the examples above come from). Below, we will go through some examples of heuristics in action, how they work – and how we can avoid falling for the traps they sometimes present.

Loss Aversion

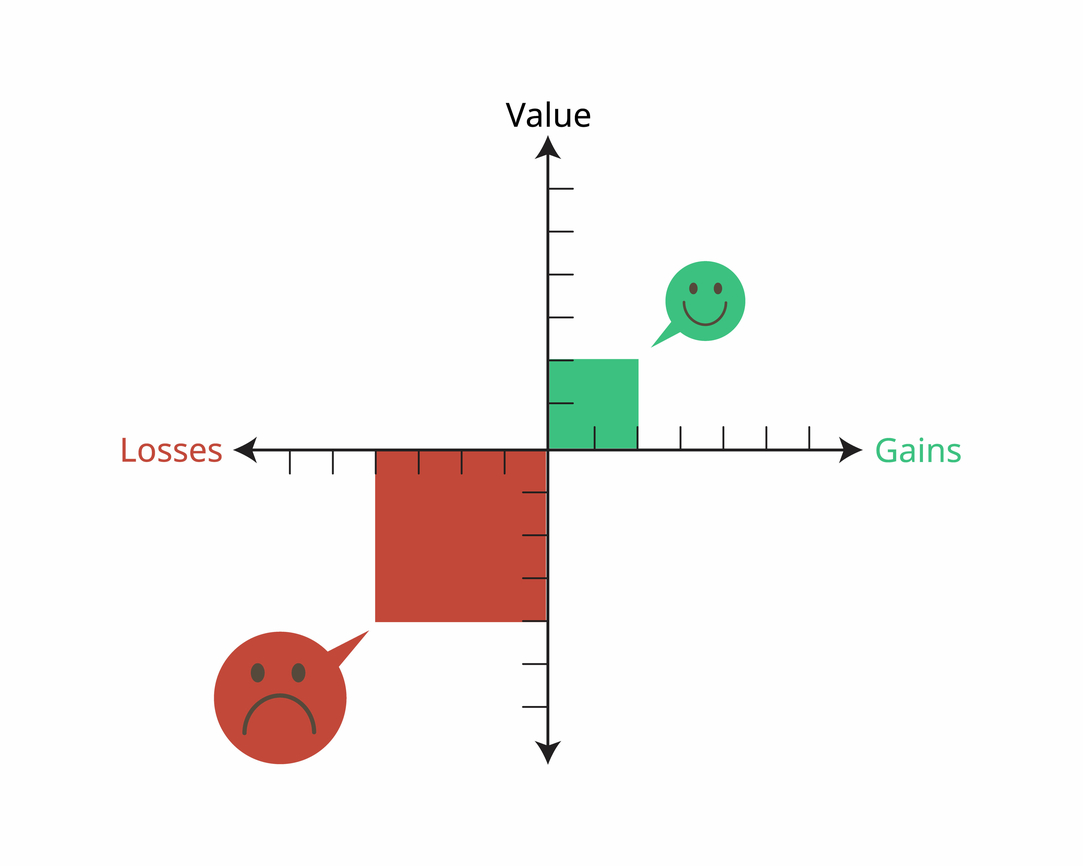

One of the most widely discussed and investigated heuristics is that of loss aversion. The name is self-explanatory – it’s a mental shortcut we often take to avoid losses. We emotionally react much more strongly to loss than we do to gains.

As an example, consider that you have $1000 to invest – there’s a 50% chance that you could get $4000 back, but there’s also a 50% chance that you might lose it all. Do you make the investment? In this case you should, as the potential gains outweigh the potential losses. Many people resist such risks, as the potential punishment of losing money feels more strong than the potential reward.

One of the central lessons from loss aversion is often used to help sell products. Trial periods help soften the monetary “loss” when purchasing something new, as the transition to purchasing can be more gradual, and we are then also faced with the potential loss of the product if we don’t continue with the purchase. We might end up spending the same amount of money for something that would have seemed too steep at first glance.

It’s of no great surprise that emotions run a lot of this. This has largely been tested through experimental paradigms that examine “willingness-to-pay” and “willingness-to-sell” (it’s also of no great surprise that typically people want to sell an object for more than buyers are willing to pay for it – or even what they are willing to pay for it [3]). A recent study carried out with iMotions shows how stimuli associated with positive emotions elicited a greater emotional response (as assessed by facial expression analysis, and ECG), and a willingness to pay more for those experiences [4].

A study carried out at Texas A&M examined attention to different attributes of roses when considering willingness-to-pay, which helped indicate which factors are most important to consumers when considering purchases of roses [5]. They also showed that the participants that were more attentive were more likely to settle on a price that considered the attributes they were presented with – whereas inattentive participants often ended up “paying” more. It can pay to pay attention.

There are of course benefits to ensuring that losses are minimal – playing it safe is a safe choice. Being too loss averse however can mean that you miss out on potential rewards – calculated risks can help you win in the long run.

Research suggests a few strategies to help you avoid the negative aspects of this heuristic. When participants are instructed to take stock of their emotions while evaluating potential losses, they tend to improve the accuracy of their judgments [6]. It can also be helpful to try and judge the situation from the outside – research suggests that considering risks for other people reduces the impact of loss aversion, and helps people make risks when they need to [7]. So, be attentive, consider your emotions, and try and be objective – you then have a better chance of taking the right risks.

Anchoring

What is the freezing point of vodka? It’s likely you don’t have an exact answer to that question, but if I was to then ask you if it’s less than -23°C (-9°F), and then asked for an exact answer, your guess would likely be closer to the truth (-27°C / -16°F in case you’re wondering). This is an example of anchoring – prior information can shape our future expectations.

Anchoring, as a heuristic, weighs down our perceptions in a certain direction – it shapes how we consider our options. For example, let’s say you’re buying a used car (although it could be anything) – the salesperson might suggest a value that seems far too high, $20,000 when you’re expecting $10,000. While you might balk at the offer, you will be cognitively anchored to that higher amount, and any reduction in the price will be seen as positive, even if the price is still above what you expect. You might think you have a good deal for getting the price down to $15,000, even though you’re paying 50% more than expected.

Our emotions can also guide this process – an initial shock at a high price, for example, can turn to a positive emotion once we drive that price down, even if it remains high. This effect can even be seen in the brain. In a 2015 study, participants first listened to a painful noise, and were asked how much money they would accept to repeat the experience – at a much higher volume. When participants were provided with a higher anchor amount – simply a large number flashed onto the screen – they asked for more money, and showed a stronger neural response just before the noise was played [8].

A study carried out by researchers from Harvard University also looked at the influence of cardiovascular responses (as measured by ECG) when navigating anchored questions [9]. Participants were led to be either encouraged or stressed – those who were stressed performed worse when answering questions with anchors in them (for example, “What is the boiling point on Mt. Everest?”, with an anchor of 212°F – (the actual answer is 68°C / 154 °F)).

The researchers also found that the ECG data predicted how well the participants would answer the questions – it mediated their stress response, and determined their performance. The best advice then for avoiding the pitfalls of anchoring, is to keep your cool – don’t let your heart guide your head.

The Gambler’s Fallacy

The gambler’s fallacy is perhaps best introduced by imagining a casino. Let’s say you’re playing on a fruit machine, and you seem to be going through a losing streak. It’s been too many losses to count, surely your luck will turn soon, right? We often have a feeling that equilibrium will eventually be reached – that our odds will eventually even out. Unfortunately, this isn’t really the case – chance only begets more chance.

As Daniel Kahneman explains: “Some familiar processes in nature obey such laws: a deviation from a stable equilibrium produces a force that restores the equilibrium. The laws of chance, in contrast, do not work that way: deviations are not canceled as sampling proceeds, they are merely diluted” [10]. While it may feel certain that luck has to balance out, there is nothing in the universe that guarantees it.

The gambler’s fallacy is a heuristic that guides us to expect that things will balance out, even when that isn’t necessarily the case. It’s not necessarily all bad news, however, as researchers have linked adherence to the gambler’s fallacy with improved general intelligence and executive function (however they also find those same people tend to perform worse on tests of decision-making, so the good news is mixed [11]).

This heuristic is a strong illustration of the common discordance between feeling and fact – just because something feels a certain way, doesn’t mean that that’s the case. Using biosensors allows for these emotions to be measured and quantified, providing insight into how we feel, and what guides them, even – maybe especially – when they’re not rationally directed.

Conclusion

Heuristics allow us to quickly make decisions – for better and for worse. They allow us to traverse our world’s quickly and efficiently, but can also lead us astray. Our emotions also act as a guiding hand for these shortcuts, which is something it pays to be mindful of. By carefully considering the information we have – and how we feel – we can make decisions that more closely reflect what we really want.

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading about heuristics – if you’d like to learn more about the intricacies of human behavior, download our free Human Behavior Guide below.

Free 52-page Human Behavior Guide

For Beginners and Intermediates

- Get accessible and comprehensive walkthrough

- Valuable human behavior research insight

- Learn how to take your research to the next level

References

1] Sternberg, R. J., Fiske, S. T., Foss, D. J. (Eds.). (2016). Scientists making a difference: One hundred eminent behavioral and brain scientists talk about their most important contributions. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

[2] Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

[3] Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., Thaler, R. H. (1990). Journal of Political Economy, 98, pp. 1325-1348.

[4] Suominen, S. (2021). Sport and Cultural Events: Willingness to Pay, Facial Expressions and Skin Response. Athens Journal of Sports, Volume 8, Issue 3, Pages 201-214.

[5] Chavez, D., Palma, M., Byrne, D., Hall, C., & Ribera, L. (2020). Willingness to Pay for Rose Attributes: Helping Provide Consumer Orientation to Breeding Programs. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 52(1), 1-15. doi:10.1017/aae.2019.28

[6] Sokol-Hessner, P., Camerer, C. F., Phelps, E. A. (2013). Emotion regulation reduces loss aversion and decreases amygdala responses to losses. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, Volume 8, Issue 3, March 2013, Pages 341–350, https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nss002

[7] Andersson, O., Holm, H. J., Tyran, J-R,, Wengström, E. (2014) Deciding for Others Reduces Loss Aversion. Management Science, 62(1):29-36.

[8] Ma Q, Li D, Shen Q, Qiu W (2015) Anchors as Semantic Primes in Value Construction: An EEG Study of the Anchoring Effect. PLoS ONE, 10(10): e0139954. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139954

[9] Kassam KS, Koslov K, Mendes WB. Decisions under distress: Stress profiles influence anchoring and adjustment. Psychological Science, 2009;20:1394–1399.

[10] Tversky, A., Kahneman, D. Belief in the law of small numbers. Psychological Bulletin, 1971, 76, 105-110

[11] Xue G, He Q, Lei X, Chen C, Liu Y, et al. (2012) The Gambler’s Fallacy Is Associated with Weak Affective Decision Making but Strong Cognitive Ability. PLOS ONE, 7(10): e47019. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047019