As part of our celebrations here in the iMotions office, we themed this quarter’s Human Behavioral Meetup group on Halloween and the biometrics of fear. It gave us a great opportunity to turn our data collection lab into a haunted house, and also provided a great chance to conduct a media study on one of mankind’s most fascinating emotions.

Halloween has its humble beginnings in the fear of the supernatural. Fear is an innate emotional response in humans: It is a neural mechanism which evolved to keep us away from things that might harm us, like snakes and spiders and lions. Today, however, our relationship with fear is a complex and contradictory one. For instance, instead of snakes and spiders and lions, we now have more modern and complex things to be afraid of, like public speaking, failure, and rejection.

Further to this, modern media has made it easier than ever to use fear as a mechanism for thrill, rather than adaptation. Many of us enjoy scaring ourselves with horror movies, haunted houses, roller coasters, and other exciting simulations of danger. How can we even try to study something as complicated and fascinating as fear?

According to Öhman and Epstein [1, 2], fear and anxiety can be two separate phenomena, described in terms of when they occur relative to a “scary” stimulus:

- Anxiety can be thought of as general, undirected physiological arousal and tension surrounding the perception of danger, in anticipation of a scary stimulus occurring (think of the creeping dread of going down a long, dark hallway).

- Fear, on the other hand, involves the sudden onset of that stimulus – the Jump Scare – producing a startle response and coping mechanisms (think of when a zombie bursts out of the closet).

The Study

How can we apply what we know about the study of fear to the media industry, where movie and television companies release hundreds of hours of scary new material each Halloween?

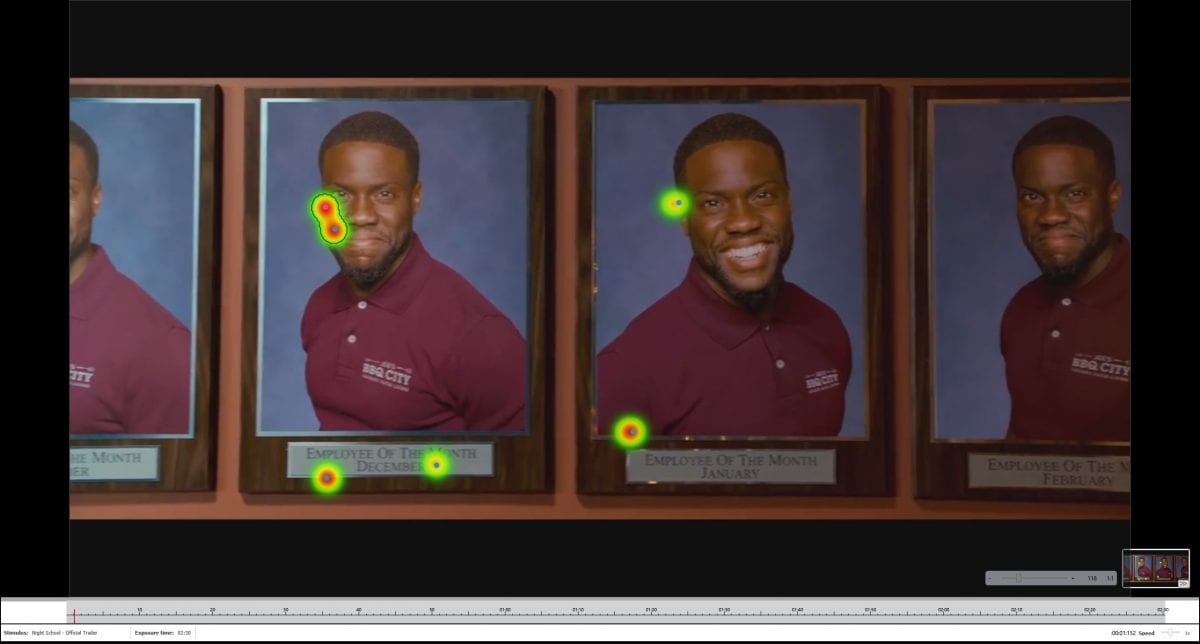

In the iMotions office, we conducted a small study wherein we invited viewers to watch three scary movie trailers (The Nun, Slender Man, and Marrowbone), to determine which trailers elicited potential biometric indicators of fear. We also tested three comedy trailers (Night School, The Spy Who Dumped Me, and Life of the Party) to serve as a comparative, “non-fear” baseline.

For sensors, we used:

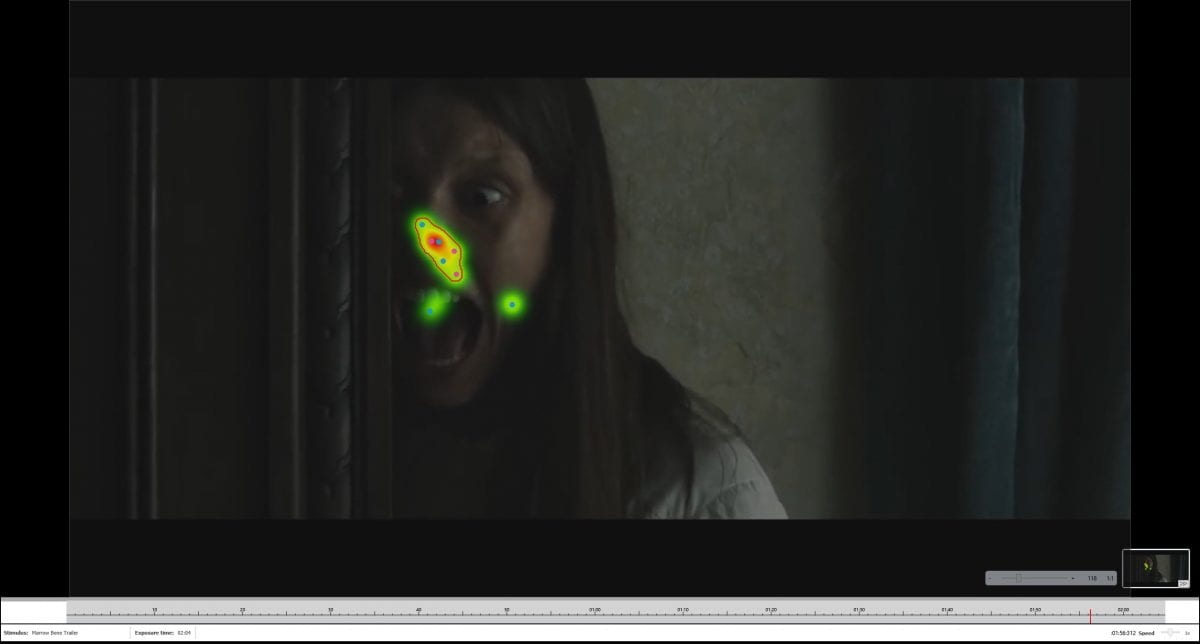

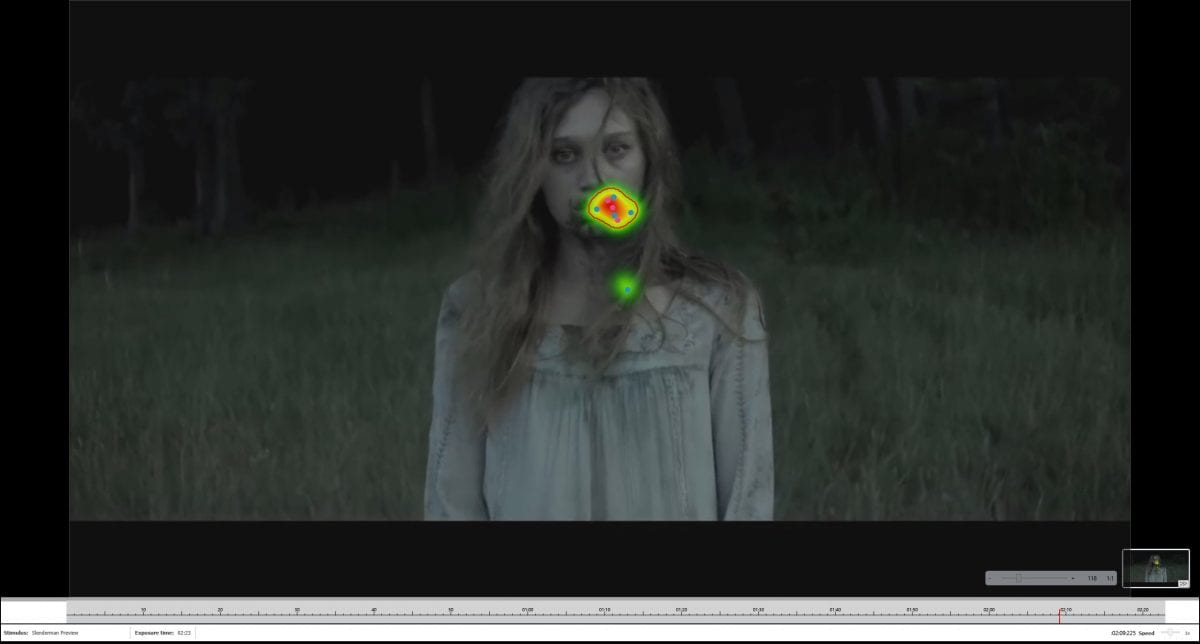

- eye tracking to assess visual attention

- galvanic skin response (GSR) to assess emotional arousal

- electroencephalography (EEG) to assess approach versus avoidance motivation via frontal alpha asymmetry

- self-reports to assess how much they liked each trailer, as well as how scary they thought each was

We hypothesized that:

- The scariest trailer would elicit the highest amount of emotional arousal, measured by GSR “peaks”;

- The scariest trailer would elicit the greatest avoidance behavioral motivation, measured through EEG frontal alpha asymmetry (FAA);

- Both of these measures would be related to viewers self-reported ratings of fear for the tested trailers.

Result 1

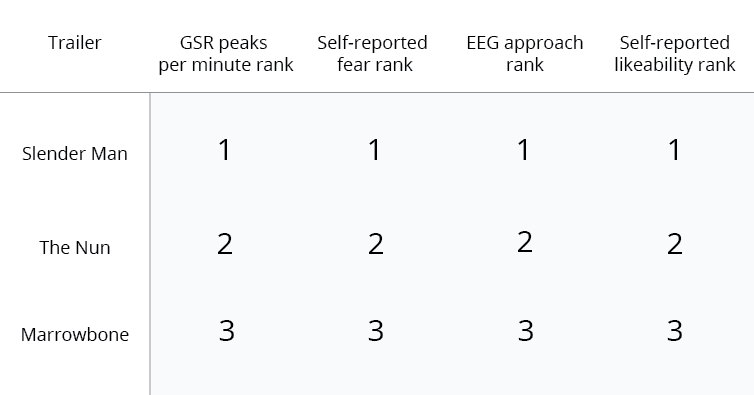

GSR Peaks/Minute Corresponds to Self-Reported Fear Ratings

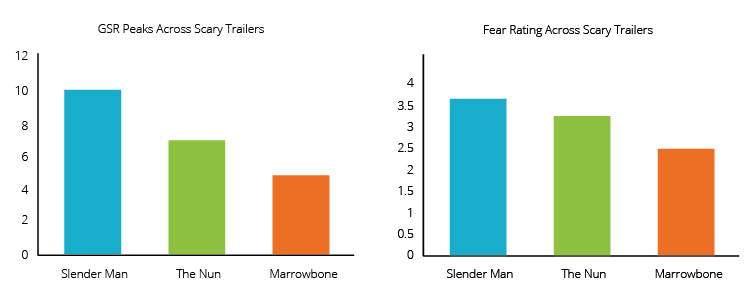

Our GSR results showed that amongst the scary trailers, Slender Man had the greatest number of GSR peaks, while Marrowbone elicited the fewest. Self-reported “fear” follows the same pattern: Viewers rated the Slender Man trailer the scariest, and the Marrowbone trailer as the least scary.

One hypothesis could be that the creative style of a horror trailer – how that trailer is designed and executed – may have a strong influence over viewers’ biometric responses. For example, the Slender Man trailer features many “jump scare” moments: Loud noises, abrupt changes in music, sudden and rapid visual cuts, and so on.

The Marrowbone trailer however takes a different approach: It features a more “ambient” horror that is rooted in the themes of the trailer, rather than relying on creative effects like jump scares. As mentioned, we also collected data on several comedy trailers, to serve as a basis of comparison. As expected, we found that the comedy trailers as a group elicited relatively lower emotional arousal than the horror trailers.

So, we have seen that scary trailers elicit a stronger emotional arousal response from viewers than comedy trailers, and it appears that the creative style of scary trailer may play an important role in audience’s biometric responses. Now, let’s turn to behavioral motivation: How can EEG enhance our understanding of how viewers experienced these trailers?

Result 2

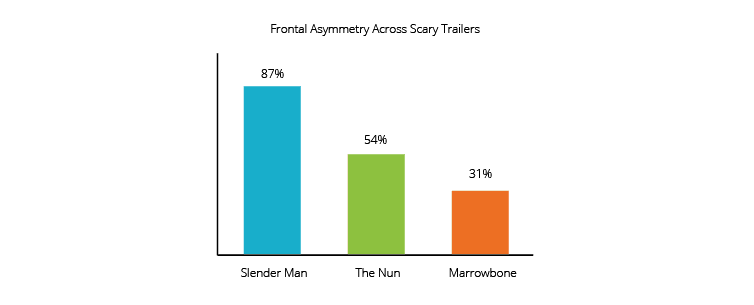

EEG Approach Motivation Corresponds to Self-Reported Likeability

At first glance, the EEG behavioral motivation results appear counter-intuitive: Slender Man was rated as by viewers as the scariest, and elicited the highest emotional arousal – but it also elicits the highest behavioral approach motivation (as measured through frontal asymmetry with EEG). Wouldn’t it be reasonable to expect that we would have seen high avoidance motivation for Slender Man?

Bear in mind what we are measuring with frontal asymmetry: It is not necessarily a measure of “good/bad”, or “scary/not scary”. Rather, frontal asymmetry reflects an individual’s cognitive motivation to take some kind of action. That motivation can come from the stimulus itself, the context in which the stimulus is experienced, the individual’s thoughts and feelings towards the stimulus and its context, or all of the above.

Now, think about the purpose of a movie trailer: To get audiences interested in, and excited by, an upcoming film. By definition, film producing companies strive to make all of their trailers – regardless of genre – motivate viewers to go to the movies (“approach”). It would be problematic if horror trailers routinely elicited avoidance motivation in viewers: If that were the case, no one would ever go to see those films!

As a final sanity check, we can look at our respondents’ self-reported liking for each trailer. Indeed, we see that Slender Man is rated as the most “likeable” of the three, coinciding with that trailer eliciting the greatest behavioral “approach” motivation.

Result 3

Greater Scariness Does Not Equal Greater Avoidance

So, to sum it up:

Slender Man, out of the three trailers, ranked highest in physiological arousal (GSR peaks/minute) and self-reported fear. However, surprisingly, it also had the highest Approach motivation based on the EEG data. Furthermore, although the self-reported likability was fairly low across the scary trailers (out of a maximum score of 5), Slender Man was still ranked the most-liked out of the scary trailers.

Far from wanting to run away from scary movies, the respondents wanted the exact opposite – the more scared they were by a movie, the greater the approach motivation they had towards it.

Thus, from our preliminary data, it appears that our hypothesis is supported: GSR can serve as a good indicator of how scary a movie trailer is. However, our second hypothesis – that scarier trailers would elicit more behavioral avoidance motivation – was not supported. Slender Man, the scariest of the horror trailers, had a relatively greater approach motivation than other horror trailers.

While this was a fun and seasonally-appropriate demonstration of how biometrics can provide insight on horror trailers, real-world research would need to account for audience demographics, genre preferences, movie viewership, and many other factors that we did not concern ourselves with. We’ll leave it to our researchers to do a true investigation.

Without a doubt, though, understanding the biometrics of fear and how they can be measured can have wide-ranging applications not just in media, but also in gaming, medical research into phobias and anxiety, and interactive experiences (think of your favorite haunted house). Hopefully, our study leaves you wanting to do some spooky science of your own!

Free 52-page Human Behavior Guide

For Beginners and Intermediates

- Get accessible and comprehensive walkthrough

- Valuable human behavior research insight

- Learn how to take your research to the next level

References

[1] Epstein, S. (1972). The nature of anxiety with emphasis upon its relationship to expectancy. In C. D. Spielberger (Ed.), Anxiety: Current trends in theory and research (Vol. 2, pp. 291–337). New York: Academic Press.

[2] Öhman A. Fear and anxiety: Evolutionary, cognitive, and clinical perspectives. In: Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, editors. Handbook of emotions. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. pp. 573–593.