Scientific rigor is the reason why science works. If this constraint and impartiality is well-maintained, then scientific findings can be relied upon, expanded upon, and built into the framework of our lives. If this isn’t the case, then it means that a lot of work can be carried out with little (or nothing) to gain from it.

While it would be nice to think that all scientists everywhere are purely impartial, or are unable to influence others in unintended ways, the truth is of course that scientists are (spoiler alert) human – and errors arise.

Researcher bias is what emerges from these errors – when scientists, intentionally or unintentionally, mislead the research they carry out.

Fail to Plan, Plan to Fail

The best-laid research plans can often go astray (to paraphrase), but the worst research plans are doomed from the start. Bad research design will ensure that, however well the experimental procedure is followed, the data won’t be of any use (this is pretty much the same as “garbage in, garbage out”).

This can arise due to unforeseen circumstances which would be difficult to anticipate, but it can also occur because the experiment wasn’t thought through properly. Having a plan that is truly measuring the variable(s) of interest, and isn’t weighted in design to give invalid results is perhaps the single most important part of the entire research process.

The Hawthorne Effect

Following on from the above, how the actual experimental procedure is followed can also drastically impact the results that are obtained. Several experiments have implicated that even the use, or avoidance, of certain words when guiding participants in a protocol can sometimes have substantial effects on their outcome. The research plan should therefore be carefully considered before implementing.

Other aspects of experimental design, such as how the investigator interacts with the participants, who the participants are, and what the participants are expected to do can impact the validity of the findings.

The Hawthorne effect is a phenomenon that occurs when the participants alter their behavior depending on what they think the study is concerned with. Some participant’s just want to please the investigator – this is full of good intentions, but ultimately dooms the research.

It may therefore help to deceive the participants, to minimize the risk of their behavior being consciously changed to conform with (or reject) the explicit research goals. In line with this, the researcher should of course avoid unintentionally leading the participant to certain answers (with leading questions, for example).

Even factors that are seemingly external to the study, such as the time of the day for the experiment, or noise around the lab, can in some circumstances systematically affect the outcome of the study.

It could be that the fire alarm is always tested on a particular day – it would then be pretty important to know this beforehand, if you’re testing a participant’s response to sound on the very same day. All of this reinforces the need for a detailed study protocol that keeps things consistent, by controlling (or at least mitigating) the factors that can affect the results in a biased way.

Study Replication

In John Bargh’s classic priming study (cited over 1600 times), participants were asked to rearrange scrambled sets of words, ostensibly to form a new sentence. The participants would then up and leave, ambling down the corridor away from the research area. This would be a boring footnote in research history if it were not for the things unseen to the participants.

For one group of participants the lists of words had one word that was always left out of the new sentences, and that word was related to the idea of being old. Further to this, when the participants made their way down the corridor, a research assistant was sat in waiting, stopwatch in hand. After the walking times had been tallied a startling conclusion was reached – participants who were exposed to the “old” stimuli seemed to walk significantly slower than the control participants (who were only exposed to neutral words).

The study appeared to suggest that even a microscopic mention of being old was enough to affect an individual’s behavior. But – and this is a very cautionary but here – the results don’t appear to hold up to further scrutiny when replicated.

A study has since shown that the original article could only be replicated under certain circumstances. Automated timing (with lasers no less), showed no difference in walking speed – the original findings couldn’t be replicated.

Taking this further also revealed that when the timing of the participants was performed manually by researchers, and when they were led to expect a more gradual pace, the slower walking speed was suddenly revealed again. This suggests that the expectations of the researchers actually shaped the outcome, one way or another.

This is all of course a rather long winded way of saying that the experimental expectations should be checked, and kept in check as much as possible. While the original study – and the priming effect in general – is still in contentious debate, it is of course good research practice to avoid any bias that could impact the results.

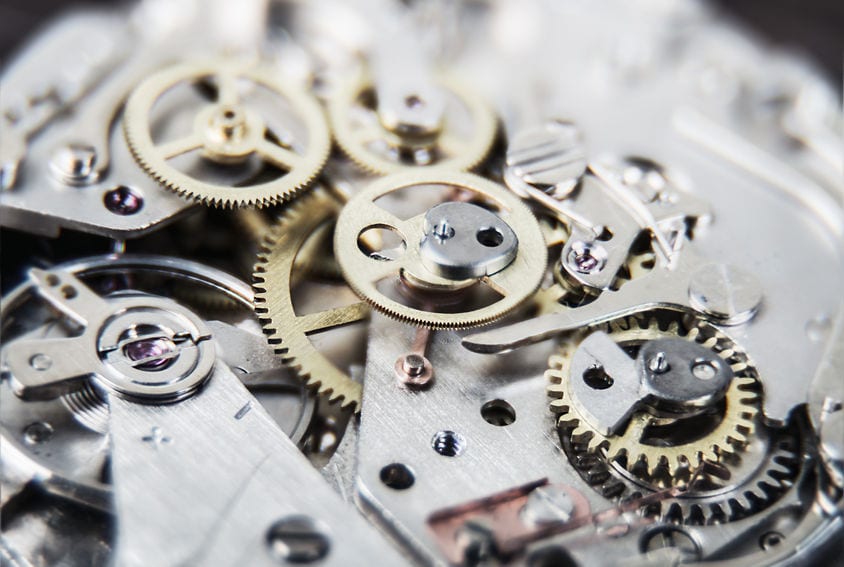

A double-blind study can readily do away with pernicious preconceptions, and automatic recordings ensure independence from the data collection. Replication of the study can also provide more validity to the original study, or will at least help reveal where any errors may lie.

Forgery, Falsification, and Fabrication

We now turn to the much more avoidable aspect of scientific research, yet one that is all too common – that of scientific misconduct through consciously changing (or entirely inventing) the results of a study.

There are many examples of this in action, and numerous reasons why such forgeries occur, yet all can be avoided by this one weird trick – not fabricating or falsifying the data. It might not sound like much wisdom, but that’s all there is to stopping this spurious effect.

Better Science

One of the ways in which researcher bias is reduced is through facilitating a clear and consistent experimental setting for the participant to act in.

Participants should be presented with the exact experimental configuration intended, and the stimuli, duration, and conditions, should be precisely defined and controlled to remove any chance of biasing researcher influence in these areas (this is something that a research platform like iMotions excels at).

This removes a large degree of experimental manipulation that might otherwise have to be implemented manually. We know that automaticity removes a great deal of unintentional researcher bias, but it also makes the life of the researcher easier too (and if the research is easier, more research can get done – something we can all agree is a great thing).

Having the data automatically synchronized and collected can also protect against any manual errors that could emerge with data collection (which, as detailed above, could do away with any potential errors obtained from using devices like stopwatches).

Multiple sensors can also help in this regard – if each sensor is in agreement with each other, then the finding is likely to be robust and reliable.

Conclusion

We can see how researcher bias occurs, and most of it can be eliminated – to do that we might need the right plan, and the right tools, but once that is complete leaves the perfect study in waiting. Putting more time and resources into implementing these steps can seem difficult in the short-term but will ultimately allow the right research to flourish. We can then move from research that misleads, to research that leads.

This article is part of our series on bias in research! We have also discussed participant bias, which you can read by clicking here, and selection bias, which you can read by clicking here.

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading about how to avoid researcher bias. If you want to learn more about how to design the perfect study, then check out our free pocket guide for experimental design below.

Free 44-page Experimental Design Guide

For Beginners and Intermediates

- Introduction to experimental methods

- Respondent management with groups and populations

- How to set up stimulus selection and arrangement