Discover how raw eye-tracking data can be transformed into effective cognitive load indicators, providing insights into how visual attention relates to mental effort. By analyzing eye movement patterns, researchers can quantify cognitive load, allowing for a better understanding of user experience and information processing.

Table of Contents

How to turn eye-tracking signals into interpretable measures of mental effort

Eye tracking systems generate large volumes of data. Every recording produces streams of gaze coordinates sampled hundreds of times per second, often alongside pupil measurements and timestamps. Seen on their own, these signals obviously do not describe cognition, they just describe movement.

The scientific challenge is not data collection, but interpretation. How do raw gaze samples become viable indicators of cognitive load? How does visual behavior turn into interpretable indices of mental effort?

This article walks through that transformation step by step, from raw gaze data to structured cognitive load indices, and explains the assumptions that make those indices meaningful.

What raw gaze data represents

At the most basic level, eye trackers record where the eyes are looking at a given moment in time. Each data point typically consists of horizontal and vertical gaze coordinates, and a timestamp.

The raw gaze data is continuous, noisy, and highly context dependent. It does not directly represent attention, comprehension, or effort. Two identical gaze traces can reflect very different cognitive states depending on task demands, stimulus properties, and individual strategies (Rayner, 1998).

Cognitive meaning does not exist at the sample level, it emerges only after the data is structured.

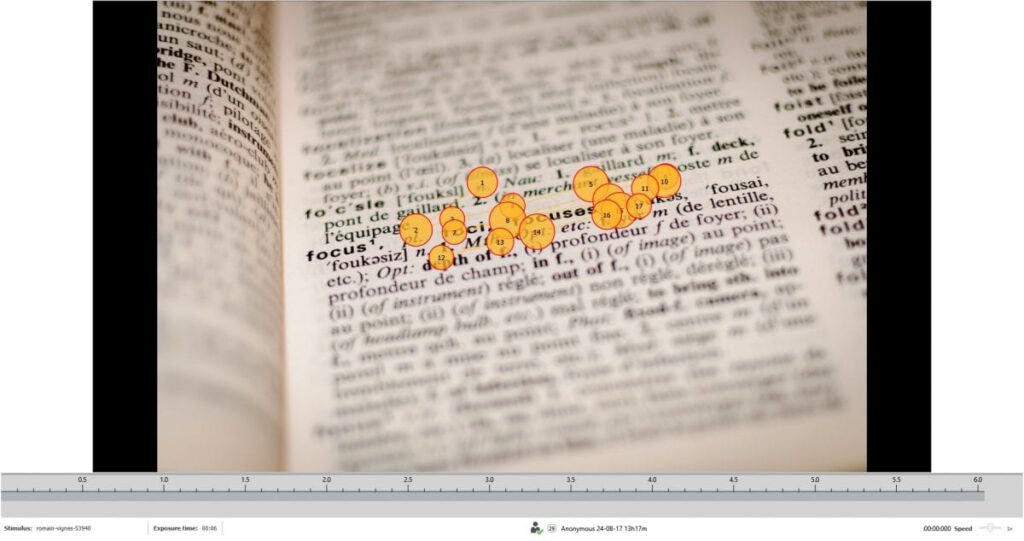

From gaze samples to eye movement events

The first major transformation step is segmentation. Raw gaze samples are grouped into functional eye movement events, most commonly fixations and saccades.

Fixations represent periods where the eyes remain relatively stable and visual information can be processed. Saccades are rapid movements between fixations during which attention processing is largely suppressed (Rayner, 2009). In reading tasks, regressions are backward saccades that return the gaze to previously viewed material.

This segmentation step matters because all higher-level interpretations depend on how events are defined. Different fixation detection algorithms can produce different fixation counts and durations from the same raw data. These differences directly affect downstream metrics and conclusions (Holmqvist et al., 2011).

Event-level metrics as indicators of processing effort

Once the gaze data is segmented into events, researchers can extract quantitative metrics. These metrics are often used as candidate indicators of cognitive load, especially in reading and visual processing tasks.

Fixation-based metrics

Longer fixation durations are commonly associated with increased processing effort (Andreou & Gkantaki, 2024). High variability in fixation duration can indicate unstable or interrupted processing. Fixation counts within specific regions of interest reveal how often information needs to be revisited.

Saccade-based metrics

Shorter saccade amplitudes and increased regression rates are commonly observed under higher processing demands, reflecting uncertainty in word recognition and increased cognitive load. More recent eye-tracking studies show that fluent reading is characterized by longer, more predictable saccades, whereas cognitively demanding reading leads to more constrained and less efficient eye movement patterns (Toki, 2024).

Temporal patterns

Cognitive load often appears not as uniform slowing, but as irregularity. Sudden pauses, repeated regressions, and disrupted scanpaths can all signal moments of increased mental effort (Hyönä et al., 2002)..

At this stage, metrics remain descriptive. They indicate behavioral patterns, but they are not yet cognitive load indices.

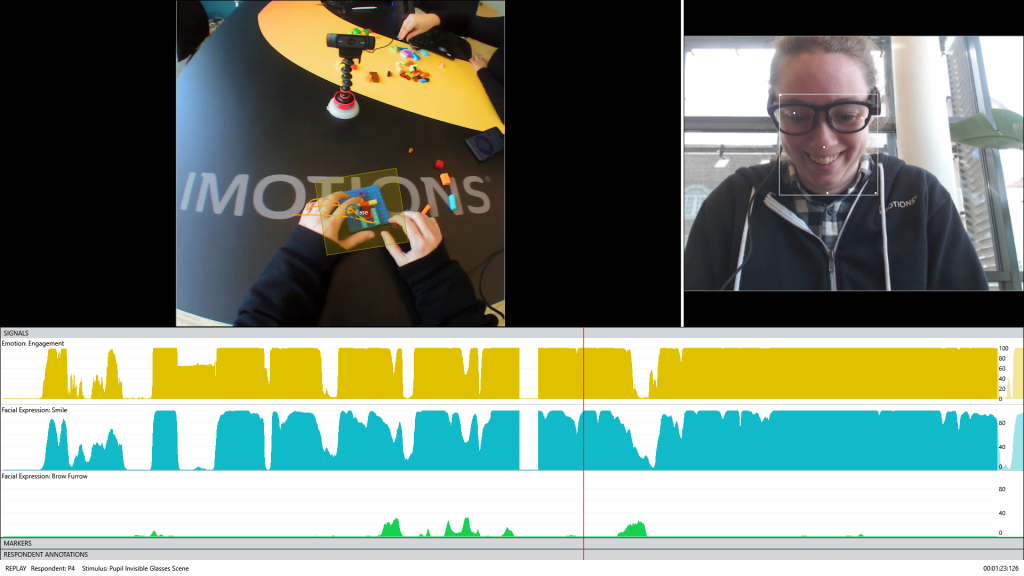

Pupillometry as a complementary signal

In addition to gaze position, many eye trackers record pupil size. Task-evoked pupil dilation is a well-established physiological correlate of mental effort (Beatty, 1982; Kahneman, 1973).

Unlike gaze direction, pupil responses are not spatial. They reflect changes in arousal and resource allocation over time. When task demands increase, pupil size often increases, even when visual input remains constant.

Pupil data requires careful control. Lighting conditions, screen brightness, fatigue, and emotional responses all influence pupil size. Demographic factors also matter: younger children and older adults often show different baseline pupil dynamics and response ranges. In clinical populations, pupillary responses may be atypical or impaired, which directly affects interpretability.

Study design choices, including text–background contrast and contrast changes between stimuli, further modulate pupil responses. For these reasons, pupil measures are typically baseline corrected and interpreted relative to task events rather than treated as absolute values (Beatty & Lucero-Wagoner, 2000).

Pupil size does not encode task difficulty directly. It reflects how much cognitive effort is being allocated at a given moment.

From metrics to indices: constructing cognitive load measures

A cognitive load index is not a single measurement. It is a structured combination of multiple metrics, aggregated and normalized in a theoretically informed way.

This process usually involves several steps:

- baseline correction to account for individual differences

- normalization across participants or conditions

- aggregation over time windows or regions of interest

- weighting metrics based on task relevance

For example, a reading-related cognitive load index might combine fixation duration, regression frequency, and pupil dilation within linguistically complex regions of a text( Sweller et al., 1998; Paas et al., 2003).

Cognitive load indices are constructed, not discovered. Their validity depends on transparent assumptions and careful alignment with task demands.

The role of task, stimulus, and individual differences

Eye-tracking metrics do not have fixed meanings. The same fixation duration can reflect deep comprehension in one task and confusion in another.

Task structure matters. Silent reading, oral reading, and visual search place different demands on the visual and cognitive systems. Stimulus design also plays a central role. Word frequency, font choice, spacing, and layout all influence eye movement behavior (Rayner, 2009).

Individual differences further complicate interpretation. Skilled readers, novice readers, and readers with dyslexia may show different eye movement patterns even when comprehension outcomes are similar. These differences often reflect compensatory strategies rather than deficits (Hyönä et al., 2002).

Cognitive load is relational. It exists only in relation to a task, a stimulus, and a participant.

What cognitive load indices can and cannot claim

When properly constructed, oculometric cognitive load indices can reveal relative changes in mental effort across conditions, designs, or task phases. They are especially useful for detecting effort that is not reflected in performance measures alone.

However, these indices do not diagnose cognitive ability, intelligence, or clinical conditions. They do not explain why load occurs. They describe how visual behavior changes when task demands increase (Paas et al., 2003).

Used carefully, cognitive load indices add explanatory depth. Used carelessly, they invite overinterpretation.

Why this transformation matters

Turning raw gaze data into cognitive load indices is one of the ways that makes eye tracking scientifically useful beyond measuring visual attention. It allows researchers to move from descriptive scanpaths to structured, comparable measures of mental effort.

This transformation supports applications in reading research, education, accessibility design, human-computer interaction, and human factors engineering. In all cases, the goal is the same: to make invisible cognitive effort measurable without relying on self-report alone.

Learn more about Cognitive Load:

Article: Understanding Cognitive Workload: What Is It and How Does It Affect Us?

Article: Exploring Mental Workload with iMotions

Product: Software Solution for Cognitive Load Measuring

References

- Beatty, J. (1982). Task-evoked pupillary responses, processing load, and the structure of processing resources. Psychological Bulletin, 91(2), 276–292.

- Beatty, J., & Lucero-Wagoner, B. (2000). The pupillary system. In J. T. Cacioppo et al. (Eds.), Handbook of Psychophysiology.

- Holmqvist, K., Nyström, M., Andersson, R., Dewhurst, R., Jarodzka, H., & van de Weijer, J. (2011). Eye Tracking: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods and Measures. Oxford University Press.

- Hyönä, J., Lorch, R. F., & Kaakinen, J. K. (2002). Individual differences in reading to summarize expository text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(1), 44–55.

- Andreou, G., & Gkantaki, M. (2024). Tracking Adults’ Eye Movements to Study Text Comprehension: A Review Article. Languages, 9(12), 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9120360

- Kahneman, D. (1973). Attention and Effort. Prentice-Hall.

- Paas, F., Tuovinen, J. E., Tabbers, H., & Van Gerven, P. W. M. (2003). Cognitive load measurement as a means to advance cognitive load theory. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 63–71.

- Toki, E. I. (2024). Using Eye-Tracking to Assess Dyslexia: A Systematic Review of Emerging Evidence. Education Sciences, 14(11), 1256. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14111256

- Rayner, K. (2009). Eye movements and attention in reading, scene perception, and visual search. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62(8), 1457–1506.

- Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (1998). Cognitive Load Theory. Springer.