The comprehensive article provides a detailed insight into the intricacies of grant writing. It covers fundamental concepts, essential strategies, and best practices needed to craft successful grant proposals effectively.

Table of Contents

Why you need to Apply For Grants

Only the best-in-class projects are funded – this is why grant writing essentials are fundamental for you and your team. Only funding makes your projects possible, enables you to purchase soft- and hardware, run studies and simulations, pay your respondents, attend conferences and visit other labs, and publish your results in peer-reviewed journals. And of course, winning grants and running a successful lab makes your unit attractive for

Undergraduate and Graduate Students, Postdocs and potential collaborators from neighboring units of your own or even other research institutions. Besides the direct benefits of having the required monetary resources to get your research done, writing successful applications also has quite beneficial “side effects” on your academic career.

Winning grants is prestigious. It is also hard work. Failure is omnipresent, and good coping strategies and your ability to deal with failure is certainly necessary to keep going and move on. Good news is that, unlike research paper submissions which have to be unique, grant applications allow you to work with templates and re-purposed text, allowing you to focus the most important parts of a proposal: Your research idea and its packaging.

In this pocket guide you will find the most important aspects when it comes to grant writing, best practices for content and style.

Let’s make sure that your next proposal is a success.

N.B. This is an excerpt from our free Grant Writing Pocket Guide. You can download your free copy below and get even more insights into the world of Grant Writing.

Free 49-page

Grant Writing Guide

For Beginners and Intermediates

- The basics and beyong

- Best practices and expert advice

- The entire process mapped out

What is a grant?

Put simply, grants are non-repayable funds handed out by the government, corporations or foundations to a recipient. In order to receive a grant, some form of grant writing – often referred to as proposal or application – is required.

You can either submit proposals to a potential funder on your own initiative, or respond to a call for proposal from the funder. Most grants fund a specific project or equipment and require a certain level of compliance and reporting.

Funding sources

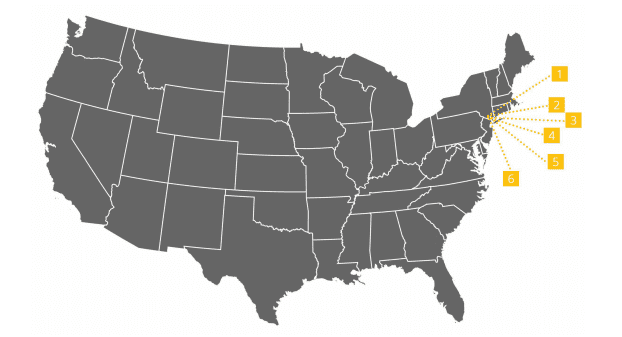

Most national funding agencies in the US are located on the East Coast:

Government funding

Major government funding sources in USA include:

1. National Science Foundation (NSF)

NSF is an independent federal agency and supports fundamental research and education in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering. Typically, NSF grants go to individuals or small groups of investigators who carry out research at their home campuses. Some grants further provide funding for mid-scale research centers, instruments, and facilities that serve researchers from many institutions. Still, others fund national-scale facilities that are shared by the research community as a whole.

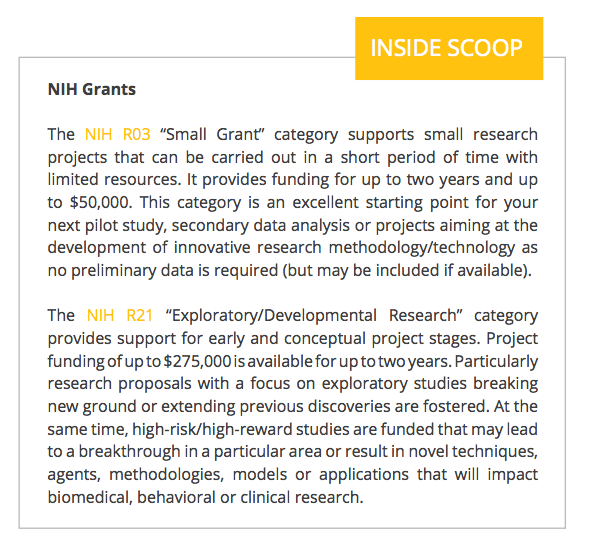

2. National Institutes of Health (NIH)

Being an agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, NIH is the largest funder of biomedical research in the world, and the primary agency of the United States government responsible for health-related projects. Additionally to research conducted on-site, NIH provides funding for extramural projects all across the US. A study of Jacobs & Lefgren (2000) shows how winning an NIH grant positively affects your research productivity.

Funding through US military

The US military primarily funds research projects through the following agencies:

3. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA)

DARPA is an agency of the U.S. Department of Defense responsible for the development of emerging technologies for use by the military. DARPA pursues strategic funding of innovative research proposals.

4. Office of Naval Research (ONR)

ONR sponsors research in core basic and applied research in new, high-risk areas investigated by multidisciplinary and multi-departmental teams. It funds topics that foster leading-edge science and attract new principal investigators and organizations.

Private grants

Private grants are given by a foundation, corporation or nongovernmental agency. Since private institutions are not buried under as much bureaucracy and red tape as the federal government, private grants can be easier to get as compared to federal grants. Examples in the human behavior research fields are:

5. The Swartz Foundation

The strategic intent of the Swartz Foundation is to integrate problem-solving approaches from physics, mathematics, electrical engineering, and computer science into neuroscience research to better understand the relationship between the human brain and mind.

6. The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation

The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation makes grants year-round to support original research and broad-based education related to science, technology, and economic performance.

Grant categories examples

It is important to understand what can and what can‘t be funded on a particular call for proposals. Basically, there are several different grant categories that differ in their funding objectives and their scope of funding.

Get familiar with:

- Research Grants

are mostly used to support discrete, specified, circumscribed research projects, typically lasting up to five years. This is NIH’s most commonly used grant program, supporting the research of teams of scientists from one or more universities. Grant funds must contribute to the direct costs of the research for which the funds were awarded, and the benefits should be directly attributable to the grant.

- Resource/Equipment Grants

typically provide funding for specific devices and instruments (such as biosensors and biomedical imaging devices like EEG, eye tracking or fNIRS systems) including software that is too expensive to be obtained through a research project grant. The purchase is typically not bound to one single project, but can be shared among several groups or scientific programs. Often, these grants cover the direct costs of the instruments, while the host institution must meet costs for maintenance, service contracts, and technical support. An example for an equipment grant is NIH’s Shared Instrumentation Grant Program. - Career Development Grants

are excellent ways to fund your project at any career stage. Particularly early-stage investigators (such as PhD students or postdocs) can gain significant momentum with funding for an intensive, supervised career development experience in the biomedical, behavioral or clinical sciences leading to research independence. Funding is provided to junior faculty members who exemplify the role of teacher-scholars through outstanding research, excellent education, and the integration of education and research within the context of the mission of their organizations. Such activities should build a firm foundation for a lifetime of leadership in integrating education and research. Examples for this type of grant are the NSF Faculty Early Career Development Program, or NIH’s various Research Career Development Awards. - Education Grants

target at supporting low-income academically talented students who are pursuing associate, baccalaureate or graduate degrees. With this grant type, the education of future scientists, engineers, and technicians is supposed to be secured by curricular and co-curricular activities affecting students’ academic advancement. For a representative example, visit NSF’s Undergraduate Education Program. - Travel Grants

provide funding for student and re-/postgraduate researchers in order to attend scientific congresses and conferences or to visit internationally recognized research institutions to collect data and meet experts to discuss preliminary results. While not that common for government funding sources, private foundations typically provide a wide variety of travel grant opportunities.

How to write a Grant

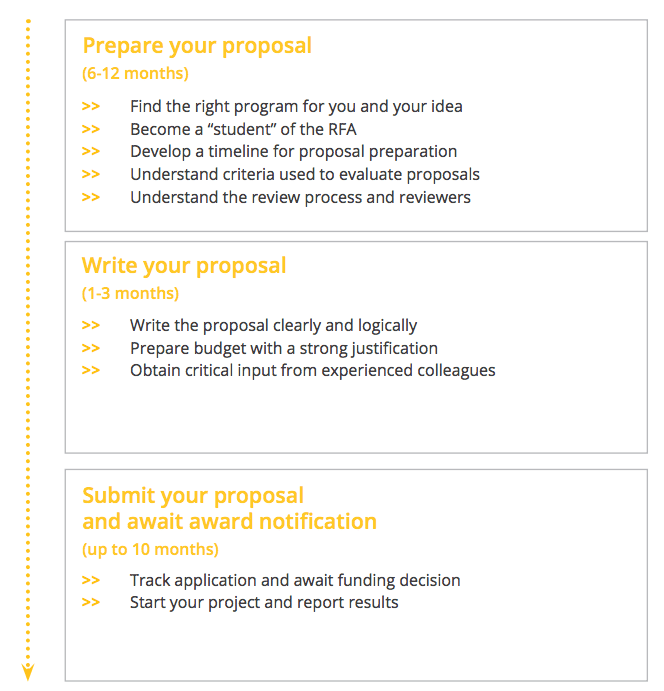

Independent of the funding source and grant category you apply for, a typical grant lifecycle comprises several common elements (or stages).

On your part it will include thorough planning, the writing of the proposal, and the submission of your grant application (along with some jittering whether your project will be funded).

To help you gain a competitive edge and prepare the best way possible,

we will get to each of them in the following sections.

What to write: Grant writing examples

Often, the difference between success and failure lies not only in the quality of the science behind your idea, but also in the quality of the proposal itself. Simply put: To make a lasting impression, your idea needs a nice, well-crafted wrapping.

Good writing will not save ideas, but bad writing will kill good ones.

(J, Kraicer, 2015; p.1)

When you compare grant applications and scientific papers, you will notice that successful proposals share the following characteristics:

>> The writing is more energetic, positive, direct, and concise.

>> Sentences are shorter, key phrases, and elements are highlighted.

>> The subject matter is easy to understand, with fewer highly technical terms.

>> Figures and tables are placed consciously.

What goes into a proposal?

An excellent grant proposal is well-prepared, thoughtfully planned, and concisely packaged. Typically, grant proposals contain the following elements:

- First page (title page)

- Abstract (summary)

- Project description

- Budget information

- Biosketch(es)

The following parts will take a closer look at the main purpose and characteristics of each proposal element and provide quick tips that will help you master the individual sections.

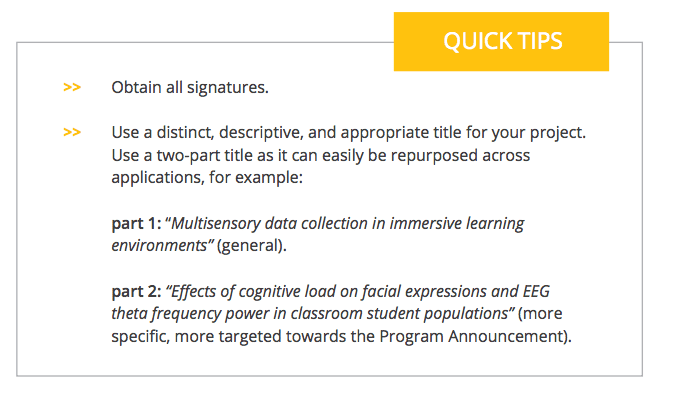

1. First page (title page)

Fill in the cover page completely and accurately (up to 10% of all applications have something missing from this page):2. Abstract (summary)

The project abstract is the most important section of your proposal as it typically is the only section that every reviewer reads. It is supposed to describe your project as concisely, accurately, and logically as possible, mostly limited to a single page. Make sure that the abstract is not just a simple summary of the proposal but stands on its own and can be understood even if separated from the rest of the application.3. Project description

The project description contains the following elements:

- Background and significance. Focus on the three questions:

1 What is known?

2 What is unknown?

3 Why is it essential to find out?

Critically evaluate existing studies and be aware that your reviewers might have contributed significantly to the existing state of knowledge. Link your current project to the missing aspects of previous research and make clear how your project will result in an advancement of the field. - Specific aims & intellectual merit. Explain how and why your current project has the potential to advance knowledge in your specific field. Phrase the intellectual merit in an impersonal and objective way, sequentially and logically. Do not include any first person references or value judgments about the merits of your work – that is for the reviewers to decide.

- Broader impact. Address in this section the broader impact of your research on neighboring fields, science and technology in general, the overall well-being of individuals and society or relationships between academia, industry, and others.

- Pilot & preliminary data. Show preliminary/pilot data to document your credibility and research experience. Pilot data helps reviewers understand that you considered side effects and hidden factors.

- Hypothesis and long-term objectives. Phrase hypotheses that can be quantified and tested. Explain how your current question has impact on long-term objectives. Why is your research significant and relevant?

- Research design and methods. Describe how you want to test the hypotheses and how you will fulfill the specific aims. Outline the research method and design to accomplish each aim and explain the rationale. Describe data collection, analysis, and interpretation. If you apply novel techniques, explain why they are superior to existing methods.

Make sure to explain thoroughly how you plan to collect and analyze the data.

4. Budget & timeline

Inexperienced writers typically propose too much and misestimate time and monetary limitations.

Always make sure to prepare a budget with strong justifications, avoiding reviewers’ impression that your project is overly ambitious or lacks focus. Make use of a project timeline and explicitly list the amount of time you and your colleagues will spend carrying out each portion of the project. Remember to align your budget with the agency’s guidelines in the Program Announcement (PA) / Request for Application (RFA) – your proposal will be judged on the degree of reasonableness.

Mention and document how your home institution will assist you in running the project (for example, providing resources that are not directly covered by the funding scheme).

5. Biosketch(es)

In this section, biosketches of all project members are listed (typically one page per person), including their contact details, current and previous positions as well as a list of their publications and contributions to science that are considered crucial for the current proposal.

The biosketch section is supposed to highlight your and your colleagues’ expertise and skills in the field. Sometimes personal statements can be added, allowing you to describe your professional and academic profile in more detail. Most likely, you can repurpose this section across several grant applications.

How to write: Style and layout

There’s a couple of simple tricks that can boost the readability of your proposal, making it much easier and fun to read for eviewers. If you present your ideas in an overly complicated way, they might lose track and skip core aspects of your proposal (Bourne & Chalupa, 2006).

Remember: Your reviewers are your strongest advocates. Provide them with the best reading experience possible.

Free 49-page

Grant Writing Guide

For Beginners and Intermediates

- The basics and beyong

- Best practices and expert advice

- The entire process mapped out

References

Bourne, P. E., & Chalupa, L. M. (2006). Ten Simple Rules for Getting Grants. PLoS Computational Biology, 2(2), e12.

Casella, P. (2007). Top 10 Things You can Do To Write and Effective Grant Application. Online resource accessed on 2016-03-27.

Darley, J. M., Zanne, M. P., & Roediger H. L. (2004, 2nd). The Compleat Academic: A Career Guide. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Grimpe, G. (2012). Extramural research grants and scientists’ funding strategies: Beggars cannot be choosers? Research Policy 41 (8), 1448-1460

Henson, K. (2004). Grant writing in higher education. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Horta, H., & Santos, J. M. (2016). The impact of publishing during PhD studies on career research publication, visibility, and collaborations. Research in Higher Education 57 (1), 28-50.

Howlett, S., & Bourque, R. (2011, 5th). Getting Funded: The complete guide to writing grant proposals. Seattle, WA: Word & Raby Publishing (book resources available online).

Jacob, B.A., & Lefgren, L. (2011). The Impact of NIH Postdoctoral Training Grants on Scientific Productivity. Research Policy 40 (6), 864-874.

Kraicer, J. (2015). The Art of Grantsmanship. Strassbourg: Human Frontier Science Program. Available online, downloaded on 2016-03-25.

Vilis, T. (1995). An example schedule for a graduate scholarship application. Online resource accessed on 2016-03-27.