The quest to understand human nature has invariably led us to explore the intricate landscape of emotions and feelings, two facets of our psychological existence that color our perceptions, influence our decisions, and shape our interactions with the world around us. Despite their significant role in our lives, emotions and feelings are often mistakenly used interchangeably in casual discourse. This conflation obscures the nuanced differences and connections between these two phenomena, which are crucial for advancing research in psychology, neuroscience, and related fields. The distinction between emotions and feelings is not just a matter of academic semantics; it is foundational to the study of emotional intelligence, impacting everything from individual well-being to the effectiveness of AI in interpreting human states.

Table of Contents

Introduction

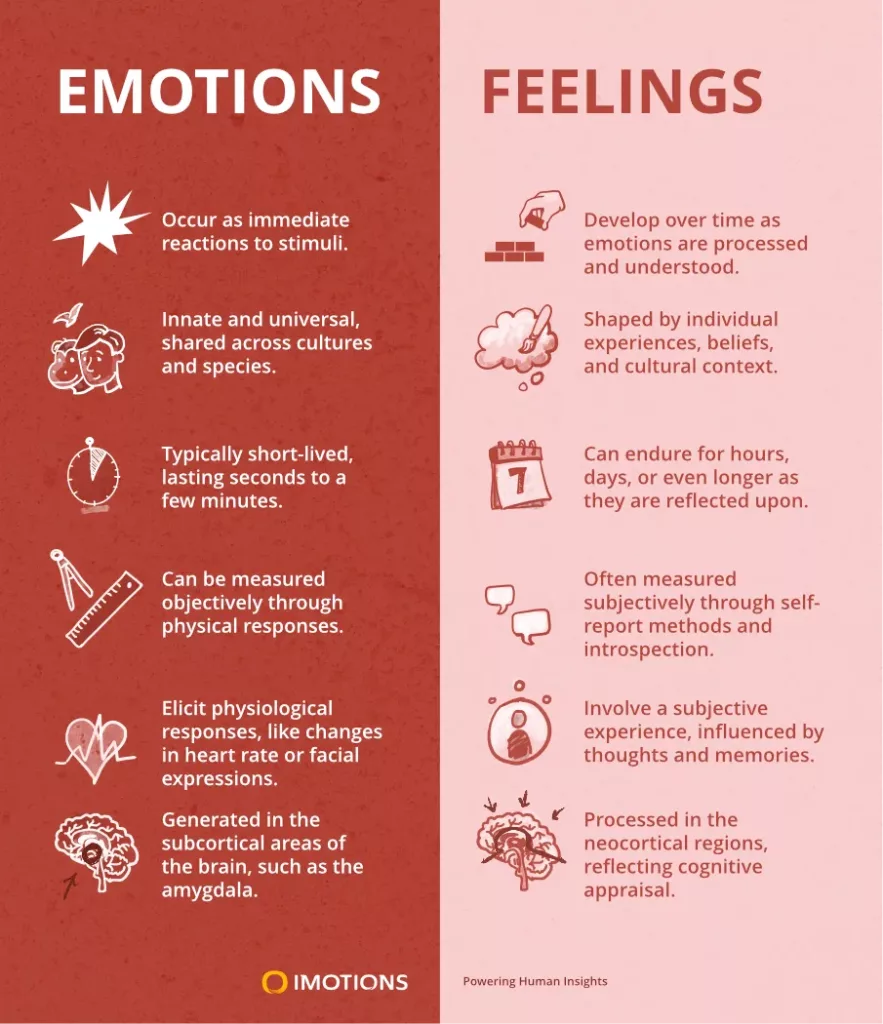

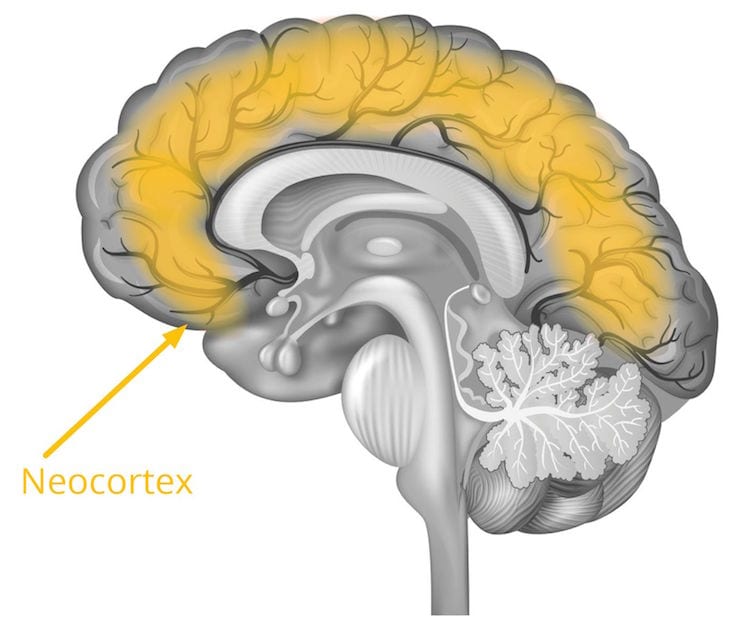

Emotions are intense, instinctual responses that arise from the brain’s subcortical regions, serving as our immediate reaction to stimuli. Feelings, on the other hand, are our subjective interpretations of these emotions, shaped by personal experiences, thoughts, and social conditioning, and are processed in the neocortical regions of the brain. Understanding the “difference between feelings and emotions” provides valuable insights into human behavior, offering a window into the complexity of our internal worlds and how these worlds influence our external actions.

This article delves into the physiological and psychological underpinnings of emotions and feelings, explores their differences, and examines the methodologies for studying them. Through a comprehensive exploration supported by current research and expert insights, we aim to clarify these concepts for academics, students, and professionals alike, enhancing our collective understanding of the human condition.

Understanding Emotions

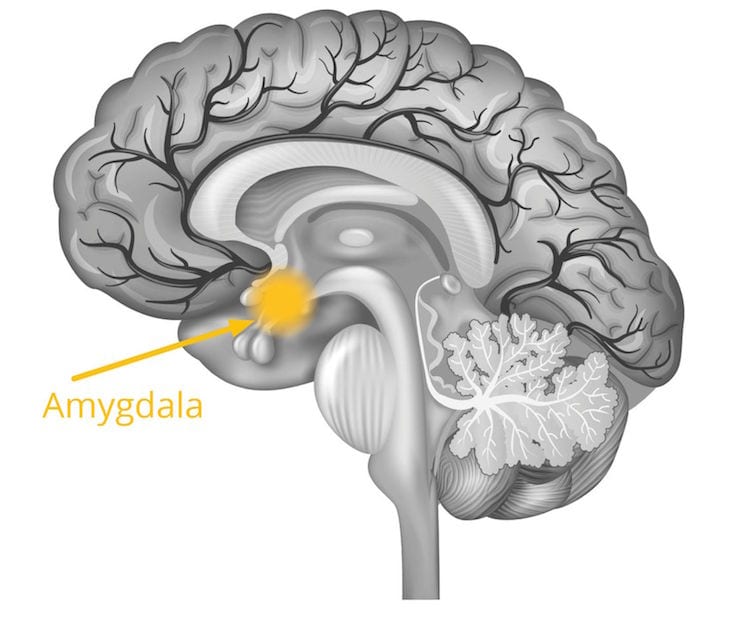

Emotions are fundamental to the human experience, serving as the bedrock upon which our perceptions, interactions, and decisions are built. They are intense, automatic responses to stimuli, rooted in the brain’s subcortical regions, such as the amygdala and the limbic system. These areas are pivotal for emotion generation, involving complex processes that affect our physical and psychological states. Understanding the biological basis and characteristics of emotions is essential for delving into their distinction from feelings, a subject of considerable interest in psychological and neuroscientific research.

The Biological Basis of Emotions

The amygdala, often referred to as the brain’s alarm system, plays a crucial role in the processing of emotions, especially those related to survival such as fear and pleasure [1]. It triggers immediate reactions to stimuli, which are manifested through various physiological responses: accelerated heartbeat, sweating, or changes in facial expressions. These reactions are part of the body’s instinctive drive to protect itself, indicating the primal nature of emotions.

Another key player in the emotional landscape is the limbic system, a network of structures involved in processing emotions and forming memories. The limbic system’s engagement ensures that emotional experiences are not only felt but also remembered, allowing individuals to learn from past experiences and react accordingly in the future [2].

Theoretical Perspectives on Emotions

Understanding emotions extends beyond their biological underpinnings to include theoretical perspectives that have evolved over time. The James-Lange Theory, one of the earliest, posits that emotions result from our perceptions of bodily reactions to stimuli. For example, we feel afraid because we run, rather than running because we are afraid [3]. In contrast, the Cannon-Bard Theory argues that emotional experiences and physiological reactions occur simultaneously, not sequentially [4].

The Schachter-Singer Theory, or the Two-Factor Theory of Emotion, introduces the idea that emotion arises from physiological arousal and cognitive labeling of that arousal, based on environmental context [5]. This theory highlights the intricate relationship between the body’s reactions, the mind’s interpretation, and the social context, foreshadowing the complex interplay between emotions and feelings.

Emotions as Physiological Responses

The physiological aspect of emotions is not only central to their experience but also to their measurement. Advances in technology have enabled researchers to measure emotions through various methods: Electroencephalography (EEG) captures brain activity, Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) visualizes blood flow changes in response to emotional stimuli, and Electrocardiography (ECG) monitors heart rate variations [6]. These objective measures provide a window into the automatic, instinctual nature of emotional responses, underscoring the difference between the physiological experience of emotions and the subjective experience of feelings.

Understanding emotions, their triggers, and their effects on the human body and mind sets the stage for exploring how these instinctive responses are interpreted as feelings. The distinction between emotions and feelings is crucial for psychological research and has profound implications for understanding human behavior, emphasizing the need for a multifaceted approach to study these complex phenomena.

Watch our free 1 hour long webinar with Dr. Brendan Murray and Dr. Jessica Wilson giving you an introduction to what we mean when we talk about “emotions”, and how to measure emotions and emotional experience in meaningful ways.

Understanding Feelings

While emotions are raw, physiological responses to stimuli, feelings represent the personal interpretation and cognitive processing of these emotional states. Feelings are the subjective experience of emotions, crafted by our thoughts, memories, and beliefs. This cognitive appraisal is what transforms a universal, instinctual emotion into a nuanced feeling that is unique to each individual. Delving into the nature of feelings, their origin, and how they are distinguished from emotions unveils the complexity of human psychology and underscores the importance of cognitive processes in emotional regulation.

The Cognitive Basis of Feelings

Feelings originate in the neocortical regions of the brain, areas responsible for higher-order functions such as thought, reasoning, and interpretation [7]. This cognitive appraisal of emotional stimuli involves assessing the significance of an emotion and assigning it a contextual meaning, transforming it into a feeling that can be articulated and analyzed. Unlike the automatic nature of emotions, feelings are shaped over time, influenced by past experiences, cultural norms, and individual belief systems.

The neocortex’s role in feelings highlights the distinction between the physical experience of emotions and the mental construction of feelings. While emotions are universally experienced and can be objectively measured, feelings are subjective and can vary greatly from person to person, even in response to the same stimulus.

From Emotions to Feelings: The Transformation Process

This transformation from emotions to feelings involves a complex interplay between the brain’s limbic system, responsible for emotion generation, and the neocortex. The process is bidirectional; not only do emotions lead to feelings, but our thoughts and feelings can also influence our emotional state [8]. For instance, merely thinking about a sad event can evoke the emotional state of sadness, demonstrating the power of cognitive processes in emotional regulation.

Measuring Feelings: Challenges and Techniques

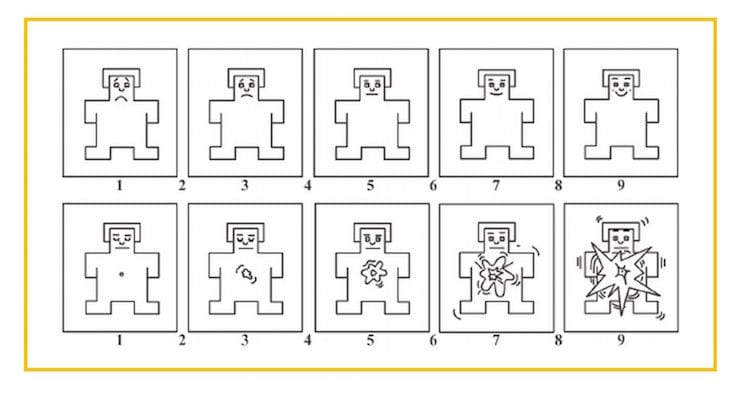

Given their subjective nature, feelings pose a challenge to measure. Unlike emotions, which can be quantified through physiological responses, feelings are often assessed through self-report measures, such as interviews, surveys, and questionnaires [9]. Tools like the Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM) provide a non-verbal pictorial assessment technique that measures the pleasure, arousal, and dominance dimensions of feelings in response to stimuli [10]. These self-report methods rely on individuals’ introspection and ability to articulate their feelings, highlighting the introspective and complex nature of feelings as opposed to the observable nature of emotions.

The Role of Feelings in Human Experience

Feelings play a pivotal role in human experience, influencing our decision-making, behavior, and interactions with others. They are essential for personal growth, allowing individuals to reflect on their emotional states, understand their reactions to various situations, and navigate their social environments more effectively. Understanding feelings, their origins, and how they differ from emotions is crucial for developing emotional intelligence and enhancing interpersonal relationships.

The Key Differences Between Feelings and Emotions

Understanding the distinction between feelings and emotions is crucial for both academic research and practical applications in psychology, neuroscience, and beyond. While closely related, these two aspects of our inner lives serve different functions and originate from different processes within the brain. By delineating the key differences, we can better understand how to measure, interpret, and respond to our emotional and feeling states.

Origin and Processing

One of the primary distinctions lies in the origin and processing of emotions and feelings within the brain. Emotions are generated in the subcortical regions, such as the amygdala and the limbic system, which are responsible for immediate, instinctual responses to stimuli [11]. These responses are universal and shared across different cultures and even species.

In contrast, feelings arise from the cortical areas of the brain, particularly the neocortex, where cognitive processing occurs. This area is responsible for the individual’s subjective experience of emotions, influenced by personal experiences, memories, and cultural conditioning [12]. The processing in the neocortex allows for the reflection and analysis of emotions, transforming them into feelings.

Physiological vs. Psychological

Emotions are associated with physiological responses that can be objectively measured, such as changes in heart rate, skin conductance, or brain activity [13]. These physical reactions are innate and serve as the body’s way of preparing for a response to various stimuli.

Feelings, on the other hand, are psychological experiences. They are the conscious awareness and interpretation of emotions, often complex and multifaceted, reflecting the individual’s personal narrative [14]. Because feelings are subjective, they are typically measured through self-report methods, such as surveys or interviews, which rely on personal introspection and articulation.

Duration and Intensity

Another difference is the duration and intensity of emotions compared to feelings. Emotions are intense but brief, lasting for seconds to minutes, and are immediately triggered by specific events or stimuli [15]. They are powerful but fleeting, reflecting the body’s immediate reaction to its environment.

Feelings, conversely, develop over a longer period and can last for hours, days, or even longer. They are less intense but more enduring, as they incorporate the emotion’s initial impact along with cognitive appraisal, making them more nuanced and reflective of the individual’s ongoing mental state [16].

Function and Role

The function of emotions is primarily adaptive, preparing the body for a rapid response to external stimuli, whether through fight, flight, or other reactions. They are crucial for survival, alerting the individual to potential dangers or opportunities [17].

Feelings serve a different purpose; they help us understand and make sense of our emotional experiences, guiding our thoughts, decisions, and behaviors in a more prolonged and reflective manner. Feelings allow for the assessment and evaluation of our emotional responses, facilitating learning and adaptation over time [18].

Methodologies for Researching Emotions and Feelings

The exploration of emotions and feelings, given their distinct natures, necessitates diverse methodologies. Research in this domain employs a range of techniques, from objective physiological measurements to subjective self-report tools, to capture the multifaceted experiences of human emotional life. Understanding these methodologies not only aids in the empirical investigation of emotions and feelings but also illuminates the intricacies of human psychological processes.

Objective Measurements of Emotions

Objective methods for researching emotions primarily focus on the physiological aspects, offering quantifiable data on the body’s response to emotional stimuli. These methods include:

- Electroencephalography (EEG): EEG measures electrical activity in the brain and is used to observe the neural underpinnings of emotional responses [19]. It is particularly effective in studying the speed and patterns of brain activity associated with different emotions.

- Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI): fMRI provides insights into the areas of the brain activated by emotional stimuli, highlighting the neural circuits involved in emotional processing [20]. This technique is invaluable for mapping the brain regions responsible for emotions and understanding their interconnections.

- Electrocardiography (ECG) and Skin Conductance: These methods measure the heart rate and skin conductance level changes associated with emotional arousal, offering direct indicators of the physiological impact of emotions [21]. They are widely used in studies aiming to quantify the intensity of emotional responses.

Subjective Measurements of Feelings

Given the internal, personal nature of feelings, research often relies on subjective methods that allow individuals to report their emotional experiences. These include:

- Surveys and Questionnaires: Standardized instruments such as the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) [22] enable researchers to assess the subjective experience of emotions and feelings over time. Such tools are essential for correlating physiological measures with personal experiences of emotion.

- Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM): SAM is a non-verbal pictorial assessment tool that measures emotional reactions to stimuli in terms of pleasure, arousal, and dominance [23]. It provides a visual scale for respondents, making it accessible for diverse populations, including those with verbal or cognitive limitations.

- Experience Sampling Methods (ESM): ESM involves asking participants to report their feelings and emotions at random intervals over time, offering insights into the dynamic nature of emotional experiences in real-life contexts [24]. This method captures the fluctuating nature of feelings and emotions as they occur naturally.

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

While these methodologies provide powerful tools for researching emotions and feelings, they also present challenges, particularly in ensuring accuracy and reliability in measuring subjective experiences. Additionally, ethical considerations must be addressed, especially in studies that might induce emotional distress in participants. Researchers are obligated to obtain informed consent, ensure confidentiality, and provide support for participants experiencing discomfort due to the study [25].

Facial Expression Analysis

In addition to the methodologies previously mentioned for objectively measuring emotions, Facial Expression Analysis stands out as a significant tool in understanding emotional responses. This method leverages advancements in technology to analyze the minute movements of facial muscles, correlating them with a range of emotions. Innovations in machine learning and computer vision have led to the development of sophisticated systems capable of accurately identifying and quantifying emotional expressions.

Facial Expression Analysis and Its Importance

Facial Expression Analysis is based on the premise that emotions are universally expressed across different cultures through similar facial expressions. This concept, initially proposed by Ekman and Friesen, laid the groundwork for understanding how emotions can be reliably inferred from facial cues [26]. Building on this, technologies like Affectiva’s AFFDEX and iMotions software have been developed to automate the detection and analysis of facial expressions, offering real-time, objective data on emotional responses.

Applications of Facial Expression Analysis

- Affectiva’s AFFDEX: AFFDEX is a facial expression recognition technology developed by Affectiva, which uses computer vision and deep learning to detect nuanced emotional states from facial cues. Research utilizing AFFDEX has demonstrated its efficacy in a range of applications, from evaluating consumer responses to advertisements to assessing emotional engagement in learning environments [27].

- iMotions Software: iMotions integrates facial expression analysis with other biosensor data, providing a comprehensive platform for emotion research. It combines facial expression data with eye tracking, EEG, and other physiological measures to offer a holistic view of the emotional experience. Studies utilizing iMotions have explored the complexity of emotional responses in scenarios ranging from psychological research to usability testing [28].

Challenges and Considerations

While Facial Expression Analysis provides a powerful tool for measuring emotional responses objectively, it is not without challenges. The accuracy of emotion detection can be affected by factors such as lighting, individual differences in expressiveness, and cultural variations in emotional expression. Moreover, ethical considerations around privacy and consent are paramount, especially when deploying these technologies in public or semi-public spaces. Researchers must navigate these challenges carefully, ensuring that their methodologies respect the dignity and privacy of participants [29].

Facial Expression Analysis, particularly through technologies like Affectiva’s AFFDEX and iMotions, represents a cutting-edge methodology for objectively measuring emotions. By capturing the subtleties of facial expressions, these tools offer valuable insights into the emotional states of individuals, complementing traditional physiological and self-report measures. The integration of Facial Expression Analysis into emotion research underscores the field’s growing sophistication and its potential to deepen our understanding of the complex interplay between physiological responses and emotional experiences.

Practical Applications: Understanding Emotions and Feelings in Various Fields

The distinction between emotions and feelings, and the methodologies for researching them, have profound implications across a variety of fields. From enhancing mental health treatment to improving marketing strategies and advancing artificial intelligence, the practical applications of this knowledge are vast and varied. This section explores how a deeper understanding of emotions and feelings can be applied to benefit society in diverse domains.

Psychology and Mental Health

In psychology and mental health, understanding emotions and feelings is fundamental to developing effective therapeutic interventions. For instance, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) relies on identifying and changing negative thought patterns that contribute to emotional distress [30]. Emotion-Focused Therapy (EFT), on the other hand, emphasizes processing and transforming maladaptive emotions [31]. These therapeutic approaches underscore the importance of differentiating between emotions (as physiological responses) and feelings (as cognitive appraisals) to foster emotional regulation and psychological well-being.

Marketing and Consumer Research

In the realm of marketing and consumer research, understanding the emotional and feeling responses of consumers to products, brands, and advertisements can significantly enhance marketing strategies. Techniques like Facial Expression Analysis, provided by Affectiva and iMotions, have been employed to assess consumer reactions in real-time, offering insights into the emotional engagement and preferences of consumers [32]. These insights help brands tailor their messaging to evoke the desired emotional responses, improving customer satisfaction and loyalty.

Education and Learning

In education, understanding emotions and feelings can enhance learning experiences and outcomes. Emotional engagement is a key predictor of learning success, and educators can use insights from emotion research to create more engaging and effective educational content [33]. Technologies that measure emotional responses, such as eye tracking and EEG, can be used to evaluate and improve the design of educational materials, making them more captivating and easier to comprehend.

Artificial Intelligence and Robotics

In artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics, incorporating emotional intelligence into systems and robots can lead to more natural and effective interactions between humans and machines. By understanding and responding to human emotions and feelings, AI systems can provide more personalized and empathetic user experiences [34]. For instance, emotion recognition technologies can enable virtual assistants and customer service bots to adjust their responses based on the user’s emotional state, improving communication and satisfaction.

Healthcare

In healthcare, recognizing and addressing the emotional and feeling states of patients can improve care delivery and patient outcomes. Emotional intelligence in healthcare providers is linked to better patient satisfaction, adherence to treatment, and overall health outcomes [35]. Moreover, technologies that objectively measure emotions can be used in clinical settings to monitor patient well-being, assess the effectiveness of treatments, and provide insights into the emotional aspects of various medical conditions.

Future Directions in the Study of Emotions and Feelings

As the fields of psychology, neuroscience, and technology continue to evolve, the study of emotions and feelings is poised for exciting advancements. These developments promise to deepen our understanding of the human mind and improve our ability to measure, interpret, and utilize emotional data in various applications. Looking ahead, several key areas are emerging as pivotal to the future exploration of emotions and feelings.

Integrating Multidisciplinary Approaches

The complexity of emotions and feelings necessitates a multidisciplinary approach, combining insights from psychology, neuroscience, computer science, and artificial intelligence (AI). Integrating these disciplines offers a more holistic understanding of how emotions and feelings arise, how they affect human behavior, and how they can be accurately measured and interpreted. Collaborations between researchers across these fields can lead to the development of more sophisticated models of emotional processing and more effective tools for emotional measurement [36].

Advancements in Emotion Measurement Technologies

Technological advancements are dramatically improving our ability to measure emotions and feelings objectively. Emerging technologies, such as wearable devices equipped with biosensors, are making it possible to track emotional states in real-time and in naturalistic settings. Additionally, developments in machine learning and computer vision are enhancing the accuracy of facial expression analysis and emotion recognition software, promising more nuanced and precise measurements of emotional responses [37]. Future research will likely focus on refining these technologies and exploring new methods for capturing the complex interplay between physiological signals and subjective emotional experiences.

Emotions in Artificial Intelligence and Human-Computer Interaction

The integration of emotional intelligence into AI and human-computer interaction is a rapidly growing area of interest. Future research aims to develop AI systems that can not only recognize human emotions accurately but also respond to them in a contextually appropriate manner [38]. This involves training algorithms on diverse datasets to understand the nuances of human emotions and developing models that can adapt to individual differences in emotional expression. Such advancements could revolutionize fields ranging from customer service and education to mental health and robotics.

Understanding Emotions and Feelings in a Cultural Context

Future studies will also delve deeper into the cultural dimensions of emotions and feelings. While emotions are often considered universal, the ways in which they are experienced, expressed, and interpreted can vary significantly across different cultural contexts [39]. Research exploring these variations can provide valuable insights into the socio-cultural factors that shape emotional experiences, contributing to more culturally sensitive approaches in psychology, marketing, and international relations.

Ethical Considerations and Privacy

As research methods for studying emotions and feelings become more advanced and invasive, ethical considerations and privacy concerns become increasingly important. Future research will need to address the ethical implications of emotional data collection and use, particularly in terms of consent, confidentiality, and the potential for misuse of emotional information [40]. Developing guidelines and standards for ethical research practices in the study of emotions and feelings will be critical to ensuring that advancements in this field are conducted responsibly and with respect for individual rights.

Conclusion

The exploration of emotions and feelings stands at the crossroads of science, technology, and the humanities, offering profound insights into the essence of human nature. This article has traversed the landscapes of emotions and feelings, from their definitions and differences to the methodologies for their study, and their practical applications across various fields. As we’ve seen, understanding the nuanced distinction between emotions and feelings is not merely academic; it has tangible implications for mental health, education, marketing, artificial intelligence, and beyond.

Looking forward, the study of emotions and feelings promises even richer insights as interdisciplinary approaches deepen, technologies advance, and our global society becomes increasingly interconnected. Ethical considerations and cultural contexts will play pivotal roles in shaping this research, ensuring it respects individual dignity while enhancing our collective understanding.

As we continue to unravel the complexities of emotions and feelings, the potential to improve human well-being, foster empathetic interactions, and create more intuitive technologies is immense. The journey to understand our inner lives is ongoing, and each discovery brings us closer to grasping the full spectrum of human experience.

Free 52-page Human Behavior Guide

For Beginners and Intermediates

- Get accessible and comprehensive walkthrough

- Valuable human behavior research insight

- Learn how to take your research to the next level

References

- LeDoux, J. (2000). Emotion circuits in the brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 23, 155-184 ↩

- Phelps, E. A. (2006). Emotion and cognition: Insights from studies of the human amygdala. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 27-53 ↩

- James, W. (1884). What is an emotion? Mind, 9(34), 188-205 ↩

- Cannon, W. B. (1927). The James-Lange theory of emotions: A critical examination and an alternative theory. The American Journal of Psychology, 39(1/4), 106-124 ↩

- Schachter, S., & Singer, J. (1962). Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychological Review, 69(5), 379-399 ↩

- Critchley, H. D. (2005). Neural mechanisms of autonomic, affective, and cognitive integration. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 493(1), 154-166 ↩

- Damasio, A. (1999). The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. Harcourt Brace ↩

- LeDoux, J. E., & Brown, R. (2017). A higher-order theory of emotional consciousness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(10), E2016-E2025 ↩

- Barrett, L. F. (2004). Feelings or words? Understanding the content in self-report ratings of experienced emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 266-281 ↩

- Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (1994). Measuring emotion: The Self-Assessment Manikin and the Semantic Differential. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 25(1), 49-59 ↩

- LeDoux, J. (2000). Emotion circuits in the brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 23, 155-184 ↩

- Damasio, A. (1999). The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. Harcourt Brace ↩

- Critchley, H. D. (2005). Neural mechanisms of autonomic, affective, and cognitive integration. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 493(1), 154-166 ↩

- Barrett, L. F. (2004). Feelings or words? Understanding the content in self-report ratings of experienced emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 266-281 ↩

- Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 6(3/4), 169-200 ↩

- Frijda, N. H. (1986). The emotions. Cambridge University Press ↩

- Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions. Oxford University Press ↩

- Immordino-Yang, M. H., & Damasio, A. (2007). We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education. Mind, Brain, and Education, 1(1), 3-10 ↩

- Davidson, R. J., & Sutton, S. K. (1995). Affective neuroscience: The emergence of a discipline. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 5(2), 217-224 ↩

- Phan, K. L., Wager, T., Taylor, S. F., & Liberzon, I. (2002). Functional neuroanatomy of emotion: A meta-analysis of emotion activation studies in PET and fMRI. NeuroImage, 16(2), 331-348 ↩

- Kreibig, S. D. (2010). Autonomic nervous system activity in emotion: A review. Biological Psychology, 84(3), 394-421 ↩

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063-1070 ↩

- Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (1994). Measuring emotion: The Self-Assessment Manikin and the Semantic Differential. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 25(1), 49-59 ↩

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Larson, R. (1987). Validity and reliability of the Experience-Sampling Method. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 175(9), 526-536 ↩

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct ↩

- Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1971). Constants across cultures in the face and emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 17(2), 124-129 ↩

- McDuff, D., Kaliouby, R. el, Senechal, T., Amr, M., Cohn, J. F., & Picard, R. (2014). Affectiva-MIT Facial Expression Dataset (AM-FED): Naturalistic and Spontaneous Facial Expressions Collected “In-the-Wild”. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops ↩

- Lewinski, P. (2015). Automated facial coding software outperforms people in recognizing neutral faces as neutral from standardized datasets. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1386 ↩

- Martinez, A. M., & Benitez-Quiroz, C. F. (2016). The reliability of facial expressions in emotion research. Emotion Review, 8(1), 58-62 ↩

- Beck, A. T. (1979). Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. Meridian ↩

- Greenberg, L. S. (2004). Emotion-focused therapy. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 11(1), 3-16 ↩

- Lewinski, P., Fransen, M. L., & Tan, E. S. H. (2014). Predicting advertising effectiveness by facial expressions in response to amusing persuasive stimuli. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 7(1), 1-14 ↩

- Immordino-Yang, M. H., & Damasio, A. (2007). We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education. Mind, Brain, and Education, 1(1), 3-10 ↩

- Picard, R. (1997). Affective Computing. MIT Press ↩

- Halpern, J. (2003). What is clinical empathy? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 18(8), 670-674 ↩

- Barrett, L. F., Mesquita, B., Ochsner, K. N., & Gross, J. J. (2007). The experience of emotion. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 373-403 ↩

- Ko, B. C. (2018). A brief review of facial emotion recognition based on visual information. Sensors, 18(2), 401 ↩

- McDuff, D., & Picard, R. (2017). Affective Computing: From Laughter to IEEE. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, 1-12 ↩

- Matsumoto, D., & Hwang, H. S. (2012). Culture and emotion: The integration of biological and cultural contributions. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43(1), 91-118 ↩

- Metcalf, J., & Crawford, K. (2016). Where are human subjects in Big Data research? The emerging ethics divide. Big Data & Society, 3(1), 2053951716650211 ↩