Explore 5 classic eye-tracking experiments for memory studies. These foundational paradigms reveal how gaze behavior reflects encoding, retrieval, working memory load, and misinformation effects, offering powerful, adaptable methods for modern cognitive and neuroscience research.

Table of Contents

Eye tracking has long been a key methodology for the scientific study of memory. While memory itself is an internal and unobservable process, eye movements provide a continuous behavioral signal that reflects how information is encoded, maintained, and retrieved. Long before the rise of large-scale neuroimaging and machine learning, researchers relied on gaze behavior to infer the structure and strength of memory representations.

What makes certain eye-tracking experiments “classic” is not their age, but their conceptual elegance. These paradigms isolate fundamental memory mechanisms while remaining flexible enough to be adapted to new stimuli, populations, and analytic techniques.

1. Visual Paired-Comparison and Novelty Preference

The Visual Paired-Comparison (VPC) task is one of the most widely used paradigms for studying recognition memory. Its logic is deceptively simple: if a participant remembers a stimulus, they will preferentially look at something new.

In a typical VPC experiment, participants are first familiarized with one or more stimuli. During the test phase, a familiar stimulus is presented alongside a novel one while eye movements are recorded. Longer fixation duration, higher fixation probability, or faster orienting toward the novel stimulus is taken as evidence of memory for the familiar item.

One of the defining strengths of the VPC paradigm is that it measures memory implicitly. Participants do not need to make an explicit decision or provide a verbal response, making it especially valuable for infant research, clinical populations, and cross-cultural studies.

In developmental research, this implicit nature is particularly powerful. Infants cannot verbally report what they remember, but their gaze behavior provides measurable evidence of learning. By tracking fixation durations across repeated exposures, researchers can quantify habituation – the gradual decline in looking time as a stimulus becomes familiar. When a novel stimulus is subsequently introduced, renewed attention (dishabituation) indicates recognition memory. This allows researchers to study developmental stages, early cognition, and memory processes long before language has emerged.

At the graduate level, VPC designs invite extensions such as manipulating retention intervals, stimulus complexity, or emotional salience. Modern studies often combine novelty-based gaze measures with pupillometry or electrophysiology to disentangle perceptual novelty from mnemonic novelty.

Read more about Visual Paired-Comparison Task here.

Infant Research

The Complete Pocket Guide

- 32 pages of comprehensive material on infant research

- Valuable infant research insights (with examples)

- Learn how to take your research to the next level

2. Scanpath Reinstatement in Scene Memory

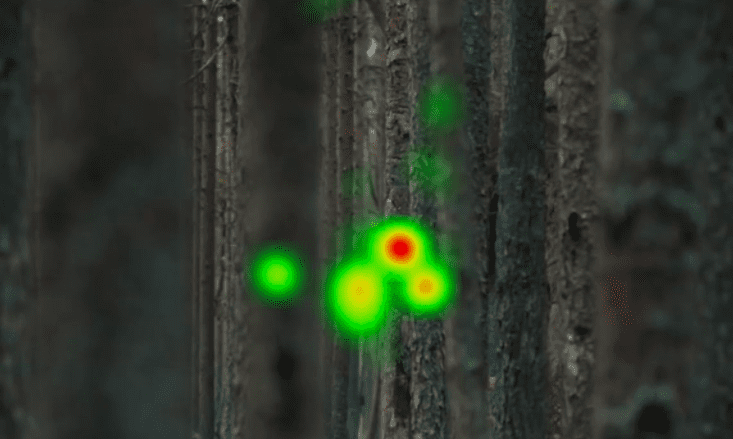

Scanpath reinstatement paradigms are built on the idea that remembering is an active process that partially recreates the perceptual and attentional dynamics of encoding. When people recall a previously seen scene, their eyes often revisit spatial locations in patterns that resemble their original scanpaths, even when the scene is no longer present.

In a typical experiment, participants study complex scenes or images while their eye movements are recorded. During later recall or recognition, scanpaths are compared between encoding and retrieval phases. Greater similarity between these scanpaths is associated with stronger memory performance.

Eye tracking is crucial here because it captures the spatiotemporal structure of memory, not just its outcome. Memory is reflected not only in what is remembered, but in how visual information is re-accessed.

For advanced research, scanpath reinstatement paradigms lend themselves to computational analyses, including scanpath similarity metrics, entropy measures, and representational similarity analysis. They are also well suited for integration with neuroimaging methods that probe hippocampal involvement in memory reactivation.

3. Subsequent Memory Effects at Encoding

Subsequent Memory Effect (SME) paradigms ask a forward-looking question: can memory success be predicted from behavior at the moment of encoding?

Participants are shown a series of stimuli while their eye movements are recorded, typically without knowing which items will later be tested. After a memory test, encoding-phase eye movements are sorted according to whether each item was remembered or forgotten.

Consistently, stimuli that are later remembered are associated with longer dwell times, more fixations, and more systematic visual exploration during encoding. These differences emerge even when participants are not consciously aware of varying their encoding strategies.

SME paradigms are particularly valuable at the graduate level because they support strong inferential logic. Encoding behavior precedes memory outcomes, making it possible to model causal relationships between attention allocation and memory formation.

Contemporary work often uses eye-tracking SMEs as inputs to predictive models, sometimes combining them with EEG or fNIRS to examine how attentional engagement interacts with neural markers of encoding.

4. Eyewitness Memory and the Misinformation Effect

Classic misinformation paradigms examine how memory for an event can be altered by misleading post-event information. Eye tracking adds a critical behavioral dimension to this research by revealing how false details are processed during encoding and retrieval.

Participants typically view a staged event, such as a simulated crime, followed by misleading narratives or images. During later memory tests, eye movements reveal how attention is allocated to true versus false details and how visual evidence accumulates during recognition decisions.

Eye-tracking data often show increased fixations and longer decision times when participants endorse false memories, highlighting dissociations between subjective confidence and objective evidence processing.

These paradigms are especially attractive for graduate research due to their ecological validity and real-world relevance. They bridge basic memory theory with applied domains such as forensic psychology and legal decision-making.

5. Working Memory Load and Visual Exploration

Working memory paradigms investigate how limited memory capacity shapes ongoing perception and attention. As memory load increases, eye movements tend to become more constrained, selective, and strategically organized.

Participants may perform tasks such as change detection or n-back paradigms while their gaze behavior is recorded. Higher memory load is typically associated with fewer saccades, longer fixations, and reduced exploratory behavior, reflecting compensatory strategies to manage cognitive demands.

Eye tracking is uniquely suited to capturing these adaptations as they happen. It reveals how participants trade off exploration and stability when cognitive resources are taxed.

At an advanced level, researchers often analyze gaze entropy, fixation dispersion, scanpaths or individual differences in strategy use. These designs also integrate well with pupillometry, allowing memory load and mental effort to be examined concurrently.

Why These Experiments Are Evergreen Classics

Despite methodological advances, these paradigms remain central to memory research because they isolate fundamental cognitive mechanisms while remaining adaptable to new questions and technologies. Each offers a clear conceptual link between eye movements and memory processes, making interpretation tractable and theory-driven.

For Master’s and PhD students, these classic designs provide more than historical context. They serve as robust frameworks on which modern analytics, multimodal measurement, and computational modeling can be layered, allowing new insights to emerge without reinventing the experimental wheel.

Eye Tracking

The Complete Pocket Guide

- 32 pages of comprehensive eye tracking material

- Valuable eye tracking research insights (with examples)

- Learn how to take your research to the next level