When you think of romance, it’s unlikely that the first thing that comes to mind is a neuroscience lab. But our ideas about attraction and love are actually being shaped there.

Not too long ago, relationships and dates would largely be limited to the people you encountered in real-life, but with the advent of online dating, all of that has changed.

Undoubtedly one of the biggest game-changers for the modern dating landscape is Tinder – simple and ubiquitous, it allows individuals to give a “yes” or a “no” to brief profiles of potential matches. Once two individuals say “yes” to each other, they become a match and can talk further.

Due to this simplicity, it’s also relatively straightforward to test – other online dating formats may come with endless forms, questionnaires, or lengthy profiles to fill out with text, while Tinder is largely driven by a single image.

With this in mind, neuromarketing researcher and iMotions client Tom van Bommel of Unravel Research in The Netherlands, set out to investigate how different features in an image can affect the desirability of a potential match, when using Tinder.

As Tom van Bommel, lead of the study put it:

“Over the past decade there’s been quite a large amount of research about how you can predict something out of brain activity – this hasn’t been done yet with dating – with one of the most important parts of life – who your partner is going to be. So that gap was quite interesting for us”.

Tom van Bommel

With an elegant experimental setup that was configured in iMotions, Tom and colleagues were able to present 27 participants with a Tinder replica, asking them to accept or reject (swiping right or left, respectively) the photos of 30 potential matches.

As the stimuli are essentially so simple, it is relatively straightforward to manipulate each image, to see how the changing of each parameter affects the outcome – if the participant desires the person in the image, or not. As Tom stated:

“We did make a Tinder replica, because we wanted to control the photos, but we didn’t have to make any concessions on realism”

The Methods

For their study, Tom and colleagues used:

- EEG (an ABM B-Alert X10)

- Eye tracking (with a 120hz eye tracker)

- Behavioral measures (accepting or rejecting the photos)

With this approach they were able to extract information about brain activity while the participants looked, and reacted to the images.

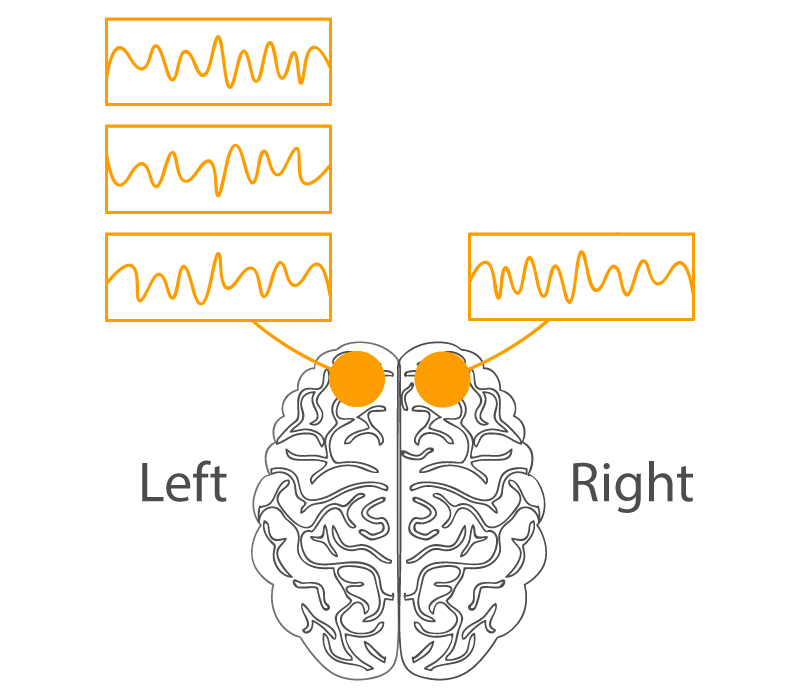

One of the crucial pieces of information that they used was a measure of prefrontal asymmetry – a recording of brain activity that relates to the difference in activity between the two frontal lobes. We’ve explained this measurement in further detail before, but in essence it indicates the approach or avoidance feelings of the participants.

ABM’s EEG device also calculates predefined metrics, such as cognitive workload, that can be used to determine how mentally taxing certain stimuli are.

By combining these measures, the researchers were able to determine the brain activity of participants in a moment-to-moment basis, and thus tie this to the images that the participants saw.

The Findings – The Science of Tinder

One of the first findings that Tom and colleagues discovered was that increased prefrontal asymmetry (in the theta band) was positively correlated with the success of each image. This showed that increased brain engagement is linked to the attractiveness of the image.

Going one step further, the researchers also looked at the level of cognitive workload, in relation to the attractiveness of the image (whether participants swiped left or right). What they found was helpful information for those seeking to improve their online profile – a correlation showed that as workload increased, the less likely the participants were to be attracted to the person in the image.

Top Tips

For those looking for more tips on how to use science to improve their dating app success, the team at ST&T worked through five parameters that are linked to the level of cognitive workload, and related how the impact of each adjusted image then fared when presented to the participants.

They found that the following affected image attractiveness:

- Contrast – the level of difference between light and dark parts of the image

- Noise – how many distracting elements there are in the image

- Other people – whether or not other people were in the image

- Composition – the headshot up close, or far away

- Facial obstruction – sunglasses!

Testing for each, the researchers found that the recipe for a perfect Tinder photo consists of:

- High contrast

- Low noise

- No other people

- Close up photo

- No sunglasses – this had the most drastic effect on the chance of match success

Examples of images that would increase cognitive workload through these parameters are shown below, as well as images that would require less workload. Images that require a large amount of cognitive processing appear less attractive within an online dating context.–

This was all made possible by using a biosensor approach – by defining the brain activity changes that relate to image success, the researchers were able to delineate which features would, and wouldn’t work. As Tom himself noted:

“iMotions made this incredibly easy to do”

By integrating multiple sensors synchronously, Tom van Bommel and team were able to construct never-before-seen insights into how our preferences are shown in a mobile dating app.

What’s next?

While these findings are certainly a goldmine for those interested in the science of attraction (or just those looking to get more dates), the researchers already have their sights set on further fields (in addition to their everyday work as a neuromarketing agency), including investigations of gambling, and stock markets.

Tom sees a brighter future for such work:

“This will definitely grow, because everytime we visit our clients or potential clients to talk about neuromarketing research, we hear so often ‘we’re going to do more with this, we have to do more with this’ – they’re really enthused”

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading about the world-first biosensor-based study of Tinder use, and feel inspired to carry out your own research. If you’d like to read an in-depth exploration of human behavior, then check out our guide below!

Free 52-page Human Behavior Guide

For Beginners and Intermediates

- Get accessible and comprehensive walkthrough

- Valuable human behavior research insight

- Learn how to take your research to the next level